A Captivating Experience.

With so many proud and capable gaming archivists already sharing their finest footage, I was eager to use what knowledge I had to thoroughly research the best possible techniques for capturing, editing and publishing using an exotic mix of hardware and software.

In an age where the 16:9 widescreen HD format was omnipresent, a minimum capture resolution of 720p (1280×720 pixels) seemed essential, though and a good deal of the titles we’d be browsing would prompt insistence that full HD 1080p (1920×1080 pixels) was the accepted norm, WQHD 1440p (2560×1440) was becoming increasingly popular and even UHD 2160p, also known as 4k (3480×2160 pixels) was enjoying a rapid uptake amidst “extremists”!

It was initially hard to think of single formula that would achieve the perfect result for every gaming scenario.

Far older games – from the nineties to the turn of the millennium – used lower resolutions with a 4:3 aspect ratio such as VGA (320×200 pixels) and SVGA (640×480) and these, many hardware and software based capture tools did not support. Additionally, the visually delectable wonderlands of 1440p and 2160p were equally hard to document in their native form due to a similar scarcity of hardware support and software based alternatives demanding unreasonable reserves of CPU power and disk space.

The Softer Approach.

Amongst the most popular means of chronicling a gamer’s triumphs and disasters were two ingenious pieces of software, FRAPS and DXTory.

Amongst the most popular means of chronicling a gamer’s triumphs and disasters were two ingenious pieces of software, FRAPS and DXTory.

Small, neat applications requiring little over a single megabyte of disk space. Following installation, these programs were executed and continued running discreetly in the system tray, with an option for them to initialize during boot up.

Various short cut keys enabled detailed data logging, including frames per second, individual frame intervals and for the recording of any Direct3d or OpenGL generated screen activity.

As with frequent derivatives, both FRAPS and DXTory intercepted the host video card’s output at frame buffer level with no external connections involved and hence, negligible risk of image degradation.

Quality was beyond reproach since further to this infallible capture technique, all recorded files were stored in a proprietary, low compression AVI format. The advantage, a crystal clear mastering of those euphoric episodes a lofty gamer’s rivals would sneeringly shun if conveyed in words alone.

The penalty, a hard drive, or several, whose very platters pleaded for redemption. FRAPS contained a modest but invaluable series of options including a choice of four fixed frame rates, one definable by the user, as well as the facility to capture audio played back by the windows mixer and record directly from a sound card’s line and microphone inputs.

DXStory went further by allowing audio to be preserved in multiple streams and then extracted for mixing and mastering during post production, indispensable for those wishing to compound their concise keystrokes with a delicately balanced live commentary. In FRAPS, footage itself could be captured in either full or half frame with resolution being dictated by the game’s internal settings.

The supposed limit was a colossal 7680×4800, higher than any other software or hardware I tested. Sadly, establishing proof of such a claim was far in excess of my technical limits and even if it hadn’t been, those avaricious AVIs would have made the process unfeasibly cumbersome and costly for regular use.

Though it relied on a custom codec, entitled FPS1, a single minute of fraps’ footage when captured at 30 frames per second in full HD 1080p, typically devoured a sliver over 3.5 gigabytes of disk space, when raising the frame rate to 60, this figure increased to just under 4.5GBs and some conventional hard drives began struggling to sustain the necessary write speeds.

Thankfully, the program was designed to dynamically adjust your frame quota in favour of a consistently smooth recording, though it’s worth nothing variable frame rates were not supported by several respected editing applications and that those which endorsed them, were also known to introduce universally exasperating tempo irregularities between the audio and video. To achieve optimum results for smoothness, FPS and resolution, a pair of fast HDDs (preferably enterprise class) configured in a RAID 0 array was all but compulsory.

Unilke FRAPS, DXStory was not inextricably bound to a natively engineered codec and permitted storing video in a selection of effective, high compression alternatives, entirely enforceable and customisable by the user. Built-in AVI multiplexing and Raw capture conversion tools were also offered as well as several menus sporting advanced tweaks that ostensibly resolved common problems or improved performance on specific systems.

In summary, both applications were admirably original, effective but ultimately expensive solutions for those wishing to extract the very best of what each could deliver. Some of their shortcomings were and continue to be shared by rivals, the most crucial of which was an innate necessity for every software based game grabber, namely that all have to be run on the same computer as the target application, consuming general system bandwidth and precious resources from the CPU and video card(s) that might otherwise be apportioned to the game itself.

SLI/Crossfire Compatibility and Setup.

A notable hindrance frequently declared to be inherent in every software recorder was their detrimental influence over multiple video cards running in SLI or Crossfire. Stories of success have been reported by fellow chroniclers, but when considering that FRAPS, and presumably all its competitors, can only intercept the data from one video card at a time, it would be logical to predict that the maximum recordable frame rate would be approximately 50% of the host system’s true optimum, assuming a dual card configuration.

To test this theory, I fired up Metro Last Light’s built in demo along with my heavily modified installation of Skyrim on the following system.

- Motherboard: Asus Rampage iV Gene

- Graphics Card(s): 2x Nvidia GTX 680s

- Hard Drive(s): 2x Samsung 256GB SSDs in RAID 0 – Dedicated recording array.

- 1x Western Digital Black 500GB – Dedicated game drive.

- Memory: 16GB Kingston HyperX 1600mhz (running at 1333mhz).

Testing Methodology.

Four batches of four tests were then conducted using our two most acclaimed screen snatchers, Fraps (no surprise) along with the more recent and equally praised DXtory.

The process was a follows. The games were loaded with each app configured and minimized in the system tray. A frame rate analysis of exactly one minute was then completed using FRAPS’s benchmarking utility (activated via the F11 key). The first of Metro Last Light’s semi-synthetic showcase and the second of a manually controlled amble through some of Skyrim’s opulent flora and fauna!

The analysis was run sixteen times in total, which broke down down as eight tests a piece for FRAPS and DXStory and two pairs of four tests per game with and without VSync and in single card and SLI modes. The results served as a baseline reference, demonstrating the video cards(s) true rendering power when neither program was carrying out a recording.

The complete cycle of 16 tests was then repeated, though this time a recording of exactly one minute was made concurrently with the frame rate analysis to assess the encumbrance each program placed upon the GPU(s) whilst capturing and the consequential reduction of speed and fluidity in both games.

The notion behind this exercise was to establish how much of a performance determent was caused by each application whilst a recording was in progress and avoid any further influence it might have over the outcome.

Consequently, for the Skyrim benchmarks when vsync was disabled, the capture rate was set to 120 fps since the video cards, whether in solo or harmony proved strong enough to sustain a pace in excess of 60fps for the entire duration. When bearing in mind fraps continuously regulates its recording frame rate in approximate accordance with the target one, there was a chance that this might also preclude the GPUs from achieving their optimum velocity, leading to skewed results and erroneous conclusions.

One minor imperfection was that FRAPS had to be running throughout both its own tests and those for DXTory since the latter lacked any facility to log frame data.

Shhhh…It’s the Softer Results!.

And so, at last, here in our old faithful data receptacle are the results…yes, it’s another table.

After some intense scrutiny, one thing was crystal clear, both FRAPS and DXTory had a statistically adverse effect on the video card’s FPS count, whether in SLI or otherwise.

However, it was also extremely interesting to discover that the extent of the deficit for each game varied dramatically and the benefits of SLI were not consistently negated, especially in the case of Metro Half light, where alarmingly, performance was crippled less by FRAPS than DXStory, despite the latter’s use of the x264 codec, which by placing less stress on the hard drive, one might have thought would yield a higher frame rate.

Of further significance was a distinct pattern indicating the encumbrance enforced when recording depended strongly on the results obtained when the capture process was idle. Superior frame rates in the latter instance triggered greater declines in the former.

The most obvious examples were the figures accumulated from the Skyrim tests conducted without vsync. DXStory imposed a damaging 72% cut on a lone GTX 680, while the penalty endured by troubled twins amounted to a monstrous 119%.

Similarly, FRAPS impeded a solo Kepler by an injurious 80% and raised the handicap to a hellacious 207% for the cohabiting couple.

Two theories arise from this, the first might suggest the hard drive employed was struggling with the task of delivering data from the video cards to its platters quickly enough to avoid the ubiquitous bottleneck, the second calls the CPU’s aptitude into question under similar suspicions.

To confirm or expunge each of these hypothetical, I used DXStory’s integral disk assessment tool to determine the Samsung array’s average speed, the result was a shade under 300 megabytes per second, which converts to 2.4 Gigabits (1 megabyte=8 megabits).

The maximum data rate during testing occurred when partnering FRAPS with Skyrim, where a single GTX 680 running at 61 fps necessitated a speed of 751 megabits per second, well under the capacity declared by the benchmark and thus, placing our drives in the the clear.

Should a sliver of doubt remain, one need only glance at DXStory’s figures from the same test, which show comparable pre and post grabbing frame quotas but much lower data rates by virtue of the x264 codec’s stiffer compression. With data rates this lean and the assets of the drives firmly established, any further charges of bottlenecking can be swiftly and sternly dismissed!

Determining the CPUs fate merely involved monitoring its core’s activities via Task Manager for the duration of each benchmark, it came as no surprise that neither application made demands burdensome enough to even approach its full and fine potential. Hence, this bizarre anomaly of larger detriments coinciding with higher frame rates when not ingesting, remained a curious mystery.

The Hardware Way

With a rich variety of hardware available, from expensive professional solutions perpetually used in the broadcasting industry, to consumer products specifically tailored for the task in hand, principal amongst my aims was to ensure that all recorded material be preserved in the highest quality I could, whilst the necessary storage space and upload times remained realistic.

Should my research prove useful to an aspiring “Let’s Player”, below are a few of the tests I ran on an eclectic array of six components complete with links to corresponding video files that you’re more than welcome to download for comparison.

The procedure involved connecting each device up to the output of an NVidia GTX Titan card, before executing four separate recordings at 720p 60hz. Two of full screen 3D benchmarks, comprising Version 3.0 of Unigine’s ornate “Heaven” and a single run of the “Times Square” demo from Crysis 2, a third of Maxon’s windowed 3D rendering test, Cinebench, and finally, an improvised Google image search for “colours”.

The operation was then duplicated at either 1080i or p and 60 or 30hz according to the hardware’s specifications. Finally, for special reference, a third iteration at 1440p 30hz was completed with the Datapath DVI-DL, the only card under review capable of .

The idea behind this methodology was to assess every possible characteristic of the picture and frame rate each card would attain when subjected to a succession of probable demands.

Use the Flash Player to access the video files.

The four tests for each card are listed in a slide-in menu on the right of the player.

Click the thumbnails to view. In each case the full HD version (1080p) is programmed to play by default, in order to view the 720p, right-click HD once, then again to swtich back to 1080p.

Grass Valley Pegasus.

This compact PCI-E x1 card was conceived by Grass Valley, a company specializing in developing and distributing technology and software for video production. Being a former devotee of Canopus (a business acquired by Grass Valley) I purchased one in late 2007 and used it mainly for archiving a combination of Sky HD broadcasts and stacks of slowly decaying VHS cassettes.

At the time it was prohibitively expensive (about £700) and only capable of capturing in a proprietary format evolved by Grass Valley themselves, known as “Canopus HQ”.

Compared to uncompressed avi, its compression ratio was approximately 5:1, meaning on average, it consumed five times less space whilst retaining a picture quality indistinguishable from the original footage, even when allowing for several generations of exporting and recompression. It was also a stable and responsive format during editing.

Unfortunately, the card’s HDMI input was the protocol’s earliest revision (1.0), and proved extremely critical, ingesting signals from a precious few number of sources. When it did work, recordings were silky smooth and utterly devoid of dropped frames over and above those already induced by exceptionally demanding games and benchmarks.

It also accepted a generous range of native computer and television resolutions and its analogue inputs (VGA, component and S-Video) were all but infallible, making it ideal for purists wishing to transfer footage directly and faithfully from historic games consoles as opposed to relying on a compromise of emulation and screen capture techniques.

But its maximum resolution of 1080i (1920×1080 interlaced) at 30hz was technically not full HD, falling short of the “gold standard” coveted by both author and viewer.

Nevertheless, alongside products with similar shortcomings, it was only fair to properly examine its potential. Using “HQ Recorder”, a simple capture application supplied with the card, and leaving every setting at its default value, quality at 720p and 60hz/FPS comfortably matched or surpassed that of every competing remedy, not too remarkable when one is mindful of the HQ codec’s extravagant bit rate.

Canopus’s HQ codec encapsulates all recorded footage within an AVI container, the format was not designed to be streamed online so each file have been provided in the rar archives below. Click once on either the thumb image or corresponding link underneath to download, be warned, these files are large even by fibre standard’s!

Unigine 720p Crysis 720p Cinebench 720p Colors 720p

Files were readily endorsed by Premier, Edius and Sony Vegas with perfectly synchronized audio and editing was a smooth, frame accurate affair.

At 1080i however, things rapidly became untenable. Xbox 360 owners claimed to have experienced great success but despite my creating a custom resolution based on the console’s output, the Pegasus frequently struggled even to recognize the signal delivered by the graphics card.

For the select few titles that produced a picture, there appeared to be no way of preventing the card from attempting to instantly de-interlace the footage it received, resulting in clusters of dropped frames compounded with irksome horizontal and vertical judder.

In conclusion, the Pegasus was a functional but overly expensive and largely inadequate means of documenting the cutting edge gamer’s greatest hits. As a general tool for preserving material from legacy gaming platforms with atypical resolutions and aspect ratios, its powers were far more persuasive.

Pros

- Very high quality results at 720p@60hz.

- HQ codec makes for stable files withf synched a/v

- Multiple analogue inputs accept a wide variety of sources and non-standard resolutions.

Cons

- HDMI input only 1.0, insufferably limited compatibility.

- 1080p@60hz not supported , even for monitoring.

- File sizes too large, conversion and re-encoding essential prior to publishing online.

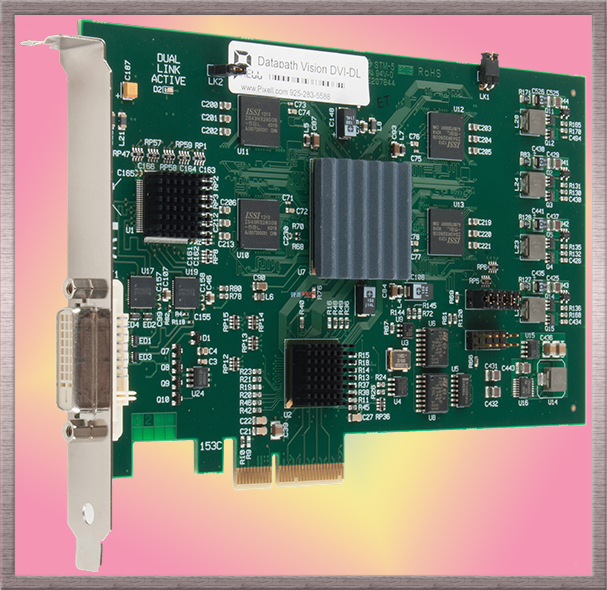

Datapath DVI-DL

Technically somewhat aloof from the competition, this industrial grade image stasher was employed by the enterprising hardware review site PC Per as a means of conducting advanced forms of frame examination and deconstruction, their aim being to assess the rendering consistency of Nvidia’s and AMD’s graphics cards. Its lord and master, Datapath, took form in 1982, and steadily emerged as a prime player in the field of creative video manipulation.

Installing the DVI-DL in a secondary PC was akin to having the facility to run FRAPS or DXtory on a dedicated capture system, a truly alluring prospect.

The card’s Spartan back plate accommodated a lonesome DVI-D input, capable of ingesting dual link resolutions of upto Quad HD 2160p (3840×2160 at 30hz), assuming the capture software and codecs that resided within were themselves equal to the challenge.

Since it flaunted full compatibility with Microsoft’s “DirectShow”, no capture application was enclosed, just the WDM driver package and a handful of fundamental configuration tools, leaving the purchaser to choose a program that also adhered to the standard and catered to their streaming, monitoring or recording aspirations.

After negotiating my way through a plethora of forum expertise and the rich array of options presented by an opulence of compliant software – in itself a steep learning curve – I eventually selected VLC Player and XSplit Broadcaster and configured all files to be recorded in the ubiquitous MPEG-4 and x264 formats, the latter being XSplit’s default and only codec.

First, the bad news, garnering a smooth recording at Quad HD using either of these forms of compression proved impossible.

XSplit permitted adding a custom template for the resolution and correctly detected the 3840×2160@30hz signal dispatched from the Titan Card but outright refused to record while VLC Player both accepted and recorded the transmission but any abundant or pronounced screen activity was accompanied by severe stuttering and pixilation. Since the CPU and hard drive had plenty left in reserve it was as though the codec itself had transcended its rendering allowance.

Progressing to the slightly better news, reducing the input resolution to 2560×1440@60hz allowed XSplit to execute a stable capture with no compromise in either frame rate or size, in other words, the recording generated was legitimate 1440p@60fps footage.

Surprisingly, even when aided by such a generous side order of pixels, the Datapath’s colour reproduction did not quite match that of the Black Magic, this could well be accounted for by XSplit’s frugal encoding rates which, even with the “ultra high” profile applied, never exceeded 25Mbps.

Datapath DVI-DL Unigine Test

Get the Flash Player to see this player.Switching to VLC player and the older MPEG-4 codec and dialing in the values to effect a 1440p output, raised both the bitrate and image quality, though file sizes began to boarder on the unpalatable and recordings would occasionally stall, depositing a steaming mound of digital junk and invoking sonorous cries of anguish.

Note that MP4 files recorded with the Datapath card using VLC player refused to stream when loaded into the flash based plug-in I have installed on this site. I tried several alternative HTML 5 players without success.

Uploading the files to Youtube allowed them to play without issue though any meaningful comparison thereafter was impossible in light Youtube’s unavoidable re-encoding process.

The files did play in Safari on an iPad/iPhone via HTML5 fallback, hence the reason for leaving the player active.

For all others wishing to inspect the original files, as with the Pegasus, please feel most welcome to download the RAR archive(s) below!

Unigine 720 & 1080p Crysis 720 & 1080p Cinebench 720 & 1080p Colors 720 & 1080p

Unigine 1440p Crysis 1440p Cinebench 1440p Colors 1440p

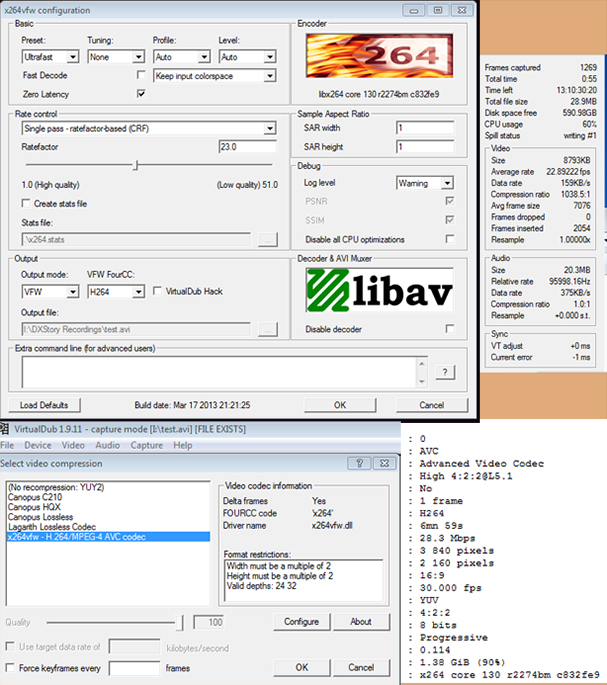

The only way to achieve an bona fide 4k recording with the Datapath that could then be edited, re-encoded and published without the worthless process of up sailing was to turn to VirtualDub and utilize exactly the same codec (x264), version and configuration as for DXTory, ensuring that audio was ensnared in uncompressed form.

Sadly, the DVI protocol’s limit of 30hz at this resolution precludes games from being run at anything above 30fps, frustrating to the casual gamer and wholly repugnant to the expert.

Pros.

- The closest to a genuine hardware based rendition of FRAPS

- Accepts the widest range of resolutions and refresh rates of any solution on test.

- 4k capture possible

Cons

- Quality entirely dependent on third party software and codecs, setup could be complicated

- Very expensive.

- No hardware assisted encoding.

- Only 30hz supported at 4K by virtue of its DVI input.

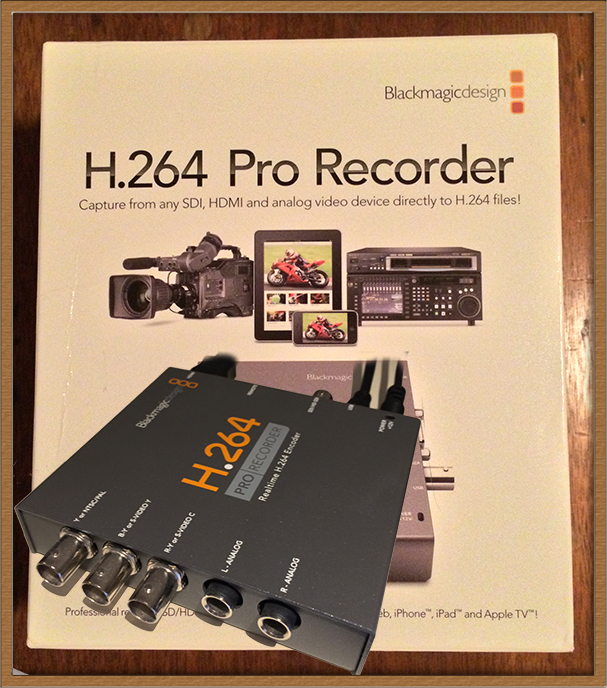

Black Magic H.264 Pro Recorder

This little box was conjured up by Black Magic Design, who over the course of several decades commencing from 1984, evolved into one of the world’s most recognized and accomplished creators and manufactures of class leading video production technology.

Rather like the Pegasus, this device was marketed as a tool for archiving footage from digital and analogue sources but utilized the more fashionable, space conserving H.264 format to garner its recordings, making it more appropriate for committing content directly to the internet but less reliable and a trifle sluggish for frame accurate editing.

It was the only hardware based to offer full HD 1080p capture at 60 frames per second – the Avermedia Live Gamer provided 60hz monitoring at this resolution but recordings were limited to 30fps while the Datapath – like Avermedia’s logical alternative, the Extreme Cap U3 – could not be considered entirely hardware-centric as it housed no on board encoding chip, relying instead on the host computer’s CPU to process all the ingested video in real time.

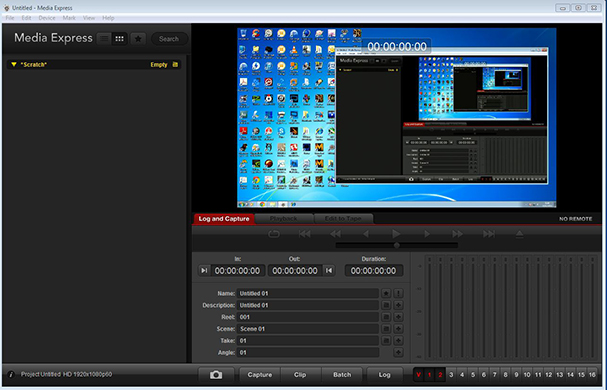

The bundled software comprised of Black Magic’s Media Express, which was used to facilitate the recordings and allowed for data rates of up to 20mbps.

Black Magic H.264 Pro Recorder Colors Test

Get the Flash Player to see this player.

In practice, quality across the board was superb, with colour reproduction notably more faithful than the Avermedia Gamer and rivalling that of the Datapath and even FRAPS and DXtory. Additionally, frame rates were consistent, audio and video in sync* and macro blocking almost negligible.

Regrettably, there were also a handful of niggles. Media Express proved far from worthy in anger, crashes would sometimes occur within seconds of initiating a capture whist at the very next attempt, things would tick over indefinitely without the merest hint of a complaint or glitch in the resultant recording.

It was also worryingly common for the capture process to spontaneously yet stealthily cease, resulting in open ended files that were neither playable or editable. This particular issue seemed exclusively linked to exiting and launching applications to and from the windows desktop, when the sudden initialization of DirectX’s overlays and fluctuations in the refresh rate (between 59 and 60hz) would cause a miniscule disruption to the signal.

In order to give this little workhorse the cleanest possible crack of the whip, I shelled out for a copy of MXlight, a third party alternative to Media Express which many claimed to be more stable and afforded a temptingly richer bit rate of 30MBps. Each benchmark was re-recorded using the highest quality settings available and the files placed alongside those encoded with Media Express. I trust all comparisons shall remain constructive!

*At the time of writing, using any drivers later than 9.6.4 and Media Express subsequent to version 3.1.2 caused corrupted frames and a gradual drift of audio and video synchronization. The sole remedy was not to update to a later driver package until the issues were fully resolved.

Pros.

- Arguably the best quality at 720p and 1080p of any solution on test.

- Files widely compatible when recordings are complete!

- Can work for hours.

Cons

- Unreliable bundled software.

- Can throw tantrums in minutes!

- HDMI input ultra sensitive to refresh rate or resolution variances.

- Limited computer resolution support for 4:3 .

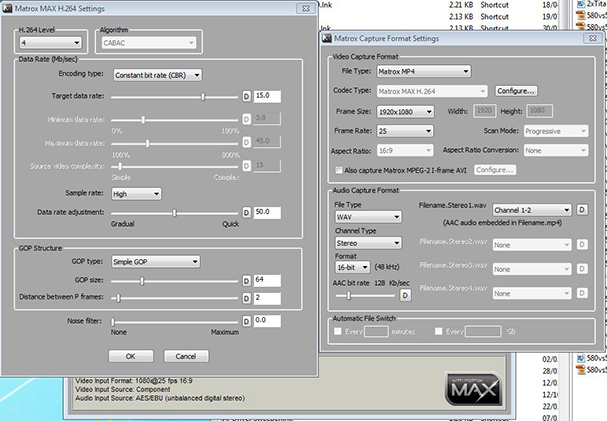

Matrox Mojito

Matrox’s Canadian headquarters incorporated two distinct business. The first and best known, Matrox Graphics Inc, began in the late 1970s to amass a history replete with diverse and visionary graphics cards, not least some of the earliest 3d accelerators. The second, Matrox Electronics System’s Ltd, consisted of two sub-divisions, Matrox “Imaging”, which specialized in frame gathering and image inspection tools and Matrox Video Systems, a renowned force in the annuls of sophisticated video artisanship.

In a review focusing on largely affordable methods of achieving a singular goal, one might well question the inclusion of this beast of a card, which was essentially a fully qualified a/v production powerhouse destined for integration with Adobe Premier.

Having relied on one to serve merely as a real time preview device in Edius, and still having it at my disposal, it would surely have verged on sin not to explore its comprehensive abilities as a capture card and judge whether or not such an augmented investment could yield the perfect long term aid.

The luxurious suite of software included with the Mojito is beyond doubt the most furnished and dependable of the bunch, bursting at the seams with a cornucopia of advanced, finely tuneable settings and a towering bit rate ceiling of 50Mbps for real-time hardware assisted MPEG4 content creation. Further format choices comprised of Matrox’s proprietary MPEG2 “I-Frame” codec and uncompressed 8 and 10bit AVI, for those with more blank space than Space.

The card’s range of ingestible resolutions was respectable but the stability of its HDMI input was a revelation when paired off against the Black Magic and superior to both the Colossus and Live Gamer HD.

Also worth referencing are the Mojito’s exceptional sound harvesting skills, over and above preserving upto 8 channels of audio embedded in an HDMI signal, there was also the option of capturing via analogue stereo XLR, or dedicated digital AES/EBU and SPDif inputs. Combining digital and analogue video and audio sources – was also possible.

Under testing, the card performed with endearing poise, even when installed in the same system as the target application. Frame rates were buttery smooth and colour definition as rich and vibrant as the Black magic, albeit at a marginally higher rate of binary interest (hard drive space…).

Matrox Mojito Unigine Test

Get the Flash Player to see this player.One glaring negative, the Mojito’s refusal to interpret a signal above 30hz at 1080p meant it suffered the same impediment as Datapath’s card encountered at 2160p, a 30fps brick wall, truly tragic for what might otherwise have reaped the gold star.

Pros.

- The most stable and feature rich on show.

- Hardware encoding.

- Advanced onboard audio capture facilities make sync issues practically impossible.

- Extensive software with detailed and useful settings. High maximum bit rate.

Cons.

- Lack of 1080p 60hz support, will only pass a 30hz signal

- You have to pay for it.

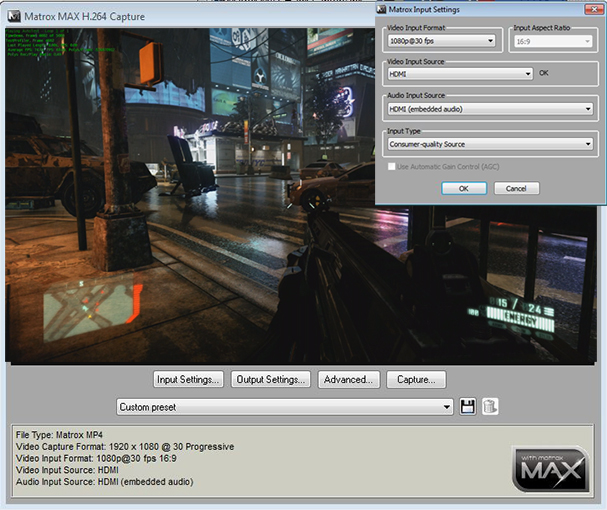

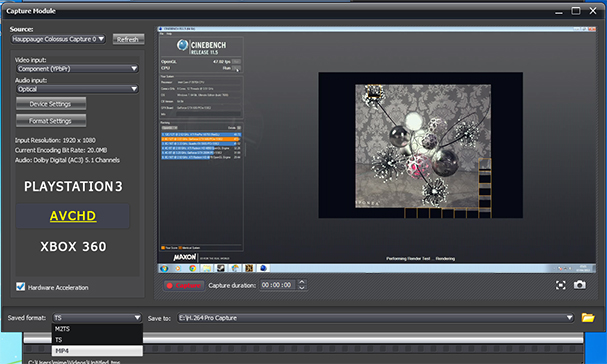

Hauppauge Colossus and Avermedia Live Gamer HD

The editorial decision to pair up these tasty contenders stems from the fact that their originators shared a similar history and philosophy. Both were initially established as prolific manufacturers of PC components designed to receive worldwide Television, Cable and Satellite broadcasts and excelled in the art marrying high-end functionality with prices the average consumer’s pockets could tolerate without the risk of a small fire

Moreover, these are the only two hardware products under scrutiny that were engineered and promoted to serve a game recordist’s precise needs.

Taiwanese based Avermedia, the youngest of the companies we have discussed, turned their attention to the gaming market in late 2011 with the release of their external “Game Capture HD”, a self governing PVR aimed squarely at the console crowd, this was swiftly followed by the Game Broadcaster HD, an internal PCI-E card with VGA, component and HDMI inputs that allowed for online streaming in addition to video capture.

The Live Gamer HD swaggered out within months and, save for the absence of analogue inputs, combined all the assets of the Broadcaster with hardware assisted H.264 encoding.

Considerably longer in the tooth, it was Hauppauge who in 2008, first realized the dreams of the High Definition archivist with its innovative “HD-PVR”, another outboard USB 2.0 device that represented sensational value at the time of its release and for several years thereafter.

Hauppauge Colossus Crysis Test

Get the Flash Player to see this player.The “Colossus” examined here, was an internal PCI-E variant that played host to identical traits, but added an HDMI input to the mix and boosted the maximum capture rate from 13 to 20MBPS. Like the Live Gamer, it alleviated the CPUs workload with a onboard encoding chip.

In contrast to Avermedia’s in-house developed “Rec Central” application, activated by a giant red button the Colossus’s supplied software, “Total Media Showbiz”, was not devised by Hauppauge themselves, but came from third party Arcsoft.

Both interfaces were accessible and practical, even if their features were rather sparse. Rec Central was better attuned to the PC gamer, with intuitive options for live streaming, recording on a secondary computer and assignable shortcut keys while Showbiz featured built-in file editing and disc authoring functions.

Recordings with each were once again made in the H.264 format with Showbiz presenting a choice of three containers (TS, MP4 and M2TS) for those wishing to immediately replay their footage on an XBOX 360 or PS3.

Quality wise, both cards yielded remarkably similar experiences.

At 720p 60hz, it was impossible to determine discrepancies. At 1080p 30hz the Live Gamer was sharper but less fluid than either itself or the Colossus at the former. A classic case of swings and roundabouts.

Avermedia Live Gamer HD UnigineTest

Get the Flash Player to see this player.One important distinction was the Live Gamer’s ability to identify a 1080p 60hz signal, then feed it straight to the user’s screen via its HDMI output at 60fps, whist concurrently recording the material at 1080p 30fps.

The feature ensured the player could monitor what was the most prevalent gaming resolution in realtime and their committed efforts were in no way disrupted by the card’s compulsion to half the frame rate prior to capture.

By comparison, the Colossus’s lack of an HDMI output limited this pass-through trickery to its component connectors and hence a maximum pixel quota and refresh rate of 1080i 60hz.

This would hardly hinder those looking to log their console’s eye candy, since both the PS3’s and Xbox 360’s native rendering skills topped out at 720p and relied on non-essential up-scaling thereafter, a feat convincingly accomplished by any modern HDTV.

Moreover, the lions share of Xbox One titles issued largely identical duties to their host’s hardware and even the PS4’s innate powers of projection rarely exceeded 900p which, when converted to 720p or 1080i at 60hz, each selectable from seductive and intuitive menus, barely marred image quality.

If used to field footage from a computer, the Achilles heel of Hauppauge’s candidate made for far less tolerable ramifications.

One had to create a custom resolution of 1080i 60hz in the GPU’s control panel, apply it on their main display, then clone the picture to one of video card’s secondary connectors with the Colossus already tethered via either of its inputs. When multiple displays are connected to a video card, and their content duplicated, the optimum resolution is always dictated by the least capable device.

Thus, the Colossus’s limitations compelled the user to carry out their chores entirely under “interlaced” conditions, a dishearteningly sluggish and visually deplorable affair when immersed in all but basic 2d applications, at least for the effervescent gamer.

Perhaps more crucially, any preserved action exhibited an all too familiar “Venetian blind” effect caused by the playback of interlaced sources on a progressive display. Excluding this was a post production operation that drastically reduced the overall quality, making 720p 60hz a better choice to begin with! PC gaming at 720p might placate the desires of many a “Let’s Player”, but having one’s desktop real estate curtailed to the dimensions of a console’s UI is surely one compromise too far.

The choice of two inputs afforded certain perks over Avermedia’s moulding, not least being able to hook a Sky Box, DVD or Blu-Ray Player to the component inputs and assemble a library of favourites sans the fears of HDCP hell, though for game capture, aside from being more cumbersome and less visually rewarding than HDMI, use of these inputs required investing in a VGA or DVI-I to component lead in order to address the absence of a regular video card’s component outputs.

The pass through function was also virtually redundant on account of its reliance on these same terminals and very few PC monitors still sporting the relevant socketary. There was the risky remedy of employing a monitor’s VGA inputs and ferrying the Colossus’s signal via a cable similar to that cited above, though a further complication existed in verifying the exact component format the monitor’s port was compatible with, there was RGB and Ypbpr….let’s just cease here and plump for HDMI!

All files generated by both cards proved compliant with most editing applications and no a/v sync imperfections were apparent.

Contrast and detail were crisp though colours seemed washed out in the face of the opposition.

Pros (Live Gamer)

- Broadest range of grabbable resolutions excluding the Datapath and Pegasus.

- Fantastic value.

- Reliable HDMI input.

- Small and neat physique, could fit inside an ITX case and make for an attractive low profile dedicated recording system.

- Stylish and intuitive software bundle

- Detected and fully usable in other applications including XSplit Broadcaster and Gamecaster

Cons

- Capture quality less stellar than the rest.

- No analogue video connections.

Pros (Colossus)

- Component inputs and outputs and

- Separate inputs for audio include both RCA and optical. Analogue video and audio sources can be combined at the time of recording.

- Like the Gamer, brilliant value.

- Reliable HDMI input

Cons

- No 1080p support (1080i 60hz maximum).

- Inferior capture quality to the more expensive alternatives, understandable but still disappointing

Results at a Glance and Conclusion

And just to finish off, one last beautiful table aptly and eloquently summarizing every pointlessly prolific phrase preceding it….actually, I just couldn’t think of anywhere else to put the damned thing.

So there you have it, all I know about the remedies of the game recordist, a proud and fascinating group of mildly obsessive digital librarians intent on conveying their fondest memories to perfect strangers. May I play now?

3DMark Firestrike - Dual GTX Titan vs. Dual GTX 680

Get the Flash Player to see this player.