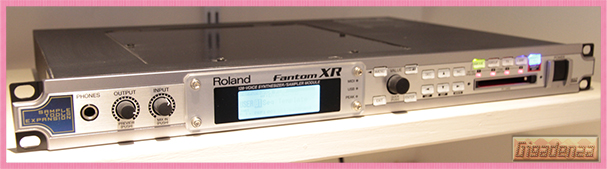

Roland Fantom XR

What! No More XVs? This Had Better Be Something…

The Fantom XR was a rack mountable reincarnation of Roland’s Fantom X6, X7 and X8 keyboards, only lacking its bigger brothers built-in sequencers, which took the form of software on the host computer at the user’s discretion. A weighty wavetable of 1408 tones was generously accommodated by 128mb of ROM with the option of bolstering both the repertoire and real estate via six 64mb SRX expansion modules to mould a 512mb myriad of vociferous supremacy.

With such a colossal a tonal palette and a maximum “polyphony” of 128 voices, it is somewhat puzzling that the Fantom’s multi-timbrel powers extended to just 16 parts, not a major inhibition but decidedly meagre next to the Sc-8850’s staggering tally of 64 and a commonly diminished faculty on Roland’s newer sonic smorgasbords.

Perhaps the typical customer’s tendency toward perpetually evolving and versatile sequencing software, compounded with their increased demand for integral sampling and editing features caused the company to shift its focus. For it is true that what the Fantom forfeited in timberality, was alleviated by monumental sound sculpting skills.

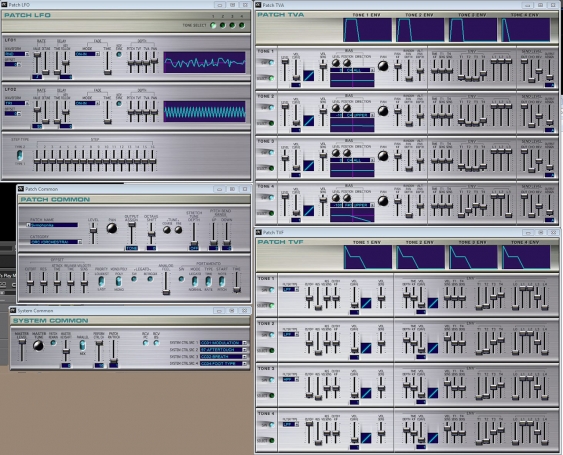

For instance, a trio of independent multi-effects engines, configurable with 78 illuminating algorithms…sentences like this are now habitually invaded by the term “such as”, then followed by several examples regarding the preceding statistic, but instead, why not just glance at these screenshots?!

Each of the parts could be assigned to one of these audio modelling processors, or bypass those and detour via two further dedicated reverb and chorus effects, or be scenically routed through both the latter and former, absorb an infusion of effects from all three, before exiting the unit through one of two pairs of 1/4 inch balanced outputs in stereo, or one of the same four jacks in mono.

The Fantom even doubled up as a self-sufficient sampler with 16mb of dedicated recording memory by default, upgradable to 528mb by means of a single 512mb stick of generic PC133 168pin SDRAM. Recordings could be made directly by hooking up stereo or mono sources to a duo of 1/4 inch balanced inputs or digital SPDif connector.

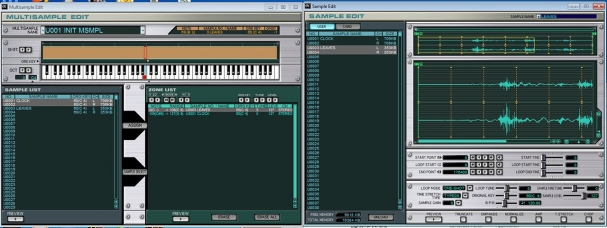

Alternatively, initiating a special “storage” mode, allowed the XR to be detected as a USB hard drive. In a frankly convoluted process that, due to an acute attack of “manual phobia” took me an entire afternoon to decipher, Wav files were dragged and dropped into a temporary folder, then “imported” and “saved” as “user” samples, where they awaited attention from a comprehensive compendium of audio manipulation and mastering tools.

Time stretching, truncating, amplifying, emphasis and normalizing were all possible using detailed proprietary editing software, which also permitted any stored samples to be designated “notes” on a virtual keyboard and “played” as an original, user tailored patch.

The procedures were nigh on identical to those carried out when compiling “soundfonts”, another rewarding trend with 90’s roots that many might have attempted or perfected. Notwithstanding, in order to safely guarantee the sanity all novices and experts, I feel compelled to refer every reader to pages 148, 149 and 150 of the user manual. Finally, use of the enclosed applications to access the XR’s gamut of functions was infinity preferable to hunching over the galaxy’s littlest LCD and negotiating merciless miniature mazes of sub-menus.

Fantom fanatics with rack real-estate to squander should ensure their acquisition is running its latest OS (version 2.02) and if necessary, download the editor – formerly part of an optional expansion kit – from this page on Roland’s American website, where one can also harvest a zip swollen with specially ported patches that earned its predecessor, the XV-5080, resounding admiration.