Perfect Synchronicity.

We begin this concise graphically pertinent piece with a literary dispute. A multitude of expressions I use to interpret facts, qualify opinions and provide the occasional twist of linguistic amusement are accompanied by a supercilious red squiggle. You know the one. The grammatical equivalent of a security guard in an Apple Store, silently scrutinizing your every move, comparing your body language and browsing habits to what his supervisor considers synonymous with those of a fully fledged “appolyte”.

You’re instinctively aware of his presence, even if his burly figure lurks behind the shop’s walls and his beady eyes are peering though an all seeing lens. Fail to solicit assistance in a timely fashion, and you will promptly be earmarked as an atypical customer, vulnerable to the “new world orchard’s” pallid preachers, their slick sales spiel and haughty insistence that every computational investment you have made prior to meeting them has been naive and misguided.

The automated dictionaries fostered in every form of desktop publishing are similarly dictatorial, the if the word isn’t part of Doctor Collins’ legendary vocabulary, it doesn’t exist, even if Professor Merriam Webster disagrees. In hastening to the point, the word “Synchronicity” was spuriously rejected by Chrome’s resident Spell Patrol despite harvesting some 5 million hits on Google. In the immeasurably esteemed view of Lord Oxford, the term has two meanings.

1: The simultaneous occurrence of events with no discernible casual connection.

2. The State of being synchronous or synchronic.

Despite the word police also declaring Syncronic as an invalid adjective, both these definitions have a significant bearing on the subject in hand. A puzzle comprising just two pieces, simple on the surface, complex at its core and one that initially confounded hardware manufacturers and driver developers in the graphics industry long before ruby and emerald tyranny took root.

Gather round we attempt to tear down an age old mystery, to pick apart a paradox of frame fragmentation that has plagued panels and perplexed players of every era, to find the formula and market the miracles of…..

“Perfect Synchronicity”

This phrase originates from a concept invented by the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung. I first heard it used by “Derren Brown” to describe the mental state of two strangers after they had simultaneously thought of exactly the same thing and scribbled identical sketches on separate pieces of paper.

In layman’s language, Jung’s philosophy declared that two or more meaningfully connected events could not be interpreted as a common coincidence.

In the context of recreational computing perfect syncronicity will occur when a video card’s pictorial compositions meet it’s monitor’s desires with flawless clarity and no waisted paint. To better understand this analogy, let us examine the flawed line of communication between GPU and VDU.

In the early 2010′ s. When an avid gamer fired up the latest steam trend and begins darting down corridors, traversing walls, strafing across terrain and amassing ammunition, both the GPU and display worked hard to fulfil their obligations. Their protocol was straightforward. An image was created by the GPU, then assigned to one of two potions of its memory, uniformly known as the “frame buffer”. As the hand-over was completed, the segment containing the data was defined as the “front or primary buffer” and immediately referred to the display.

At the same juncture, the GPU went on to forge the next frame in the sequence and allocated itself a further portion of VRAM in which to store it, known as the “back or secondary” buffer. As soon as that image has been finalized, these two segments swapped places and the entire cycle repeated itself until our gamer was exhausted. The procedure, appropriately entitled “double buffering”, ensured the GPU could continuously generate new frames whist those already composed were always available for the monitor to scan.

What could possibly go awry in implementing such a simple and logical modus operandi? As it happens, a fair bit. For all his toil and tolerance, our monitor was not the most versatile creature and could only receive frames from the video card at a specific number of intervals per second, collectively defined as the refresh rate. If these did not coincide with the GPU’s activities, any frame that arrived in the middle of an interval was effectively sliced in two, resulting in fragments of certain frames being combined with others and presenting the player with a crudely composited image. A profoundly undesirable phenomenon aptly christened “tearing”.

If we think of the display’s refresh cycles as a set of revolving doors operating at a fixed speed and imagine the frames to be varying numbers of people passing though them, we can understand that as frame rates rose, the problem would become more pronounced since there was statistically higher risk of images being trapped and torn between scans, just as several people might pile up in a single division of the doors. In serious cases, as many four incomplete frames could be visible at once. Higher refresh rates helped to alleviate the problem but only by lengthening the odds of its symptoms, as opposed to addressing the underlying cause. Were there any more decisive remedies? Perhaps, though as ever, the notorious volatility of the gaming community ensured that a Paladin’s cure was a Barbarian’s curse.

To Sync or to Sheer, That is the Question.

When I said Sync, I of course meant VSync but that would have sounded rubbish. Ever seen a live interview where the host has finished a question and the guest nods there head for embarrassing seconds while the audio bounces off a satellite and into the space between their ears? No doubt you’ve witnessed the wonders of cutting edge communication. Those hyper-intelligent handsets that that allow us to hold conversions without ever completing a sentence?

Vsync in its traditional form instructed the GPU to never dispatch images at a frequency that exceeded the monitor’s refresh rate and moreover, to forward them in strict accordance with the latter’s “vertical blank” signal. Applying our analogy, this was the display’s way of saying to its willing supplier, “I’ve finished my sentence”, “over to you”. As the frame rate was now wholly dictated by the monitor’s requests, it was no longer possible for our player to suffer the visual penalties imposed by partially drawn images.

In short, no tears no teers (sic!) correct? Not quite, the advantage came at a price. Firstly, if the game was relatively lenient on resources, performance could be heavily impeded by the display. A monitor with a refresh rate of 60hz, was restricted to scanning 60 frames per second, irrespective of the GPU’s abilities. In scenarios where the video card would normally be processing frames at a far higher rate, this meant that its frame buffers were filled to capacity in a very short period and the GPU was forced to wait for pre-rendered data to be cleared before it duties could continue. To those with screens equipped to refresh at 120 and 144hz this was less of a hindrance since these bestowed an elevated workload on the GPU.

However, this in turn gave rise to a second and more troubling anomaly. If the game was exceptionally onerous and the GPU was unable to keep pace with the monitor’s demands, it was forced to regulate its frame rate in fixed steps derived from factors of the refresh rate. Hence, 60fps could not be subtly reduced to 50 then boosted to 56, it had to be rounded down in whole factors, to 30, 20, 15 and so on, then back up via the same sequence. The net effect was two aggravating side-effects. Stuttering and input lag. Often severe enough to mitigate the advantages of sheer and tear free motion.

Adapt and Survive?

Adaptive sync was Nvidia’s first official workaround and emerged within drivers that accompanied the launch of it’s GTX 680 in 2012. As the name suggests it worked with a modicum of intelligence, automatically activating VSync whenever the frame rate matched the monitor’s extremities and switching it it off it at all other times. This removed a sizeable percentage of tearing but at less of a cost to performance due to the GPU being allowed manage its frame rate in a “step-less” fashion. It was a fair compromise but far from a definitive and given the consequences already covered, the reasons are self-evident.

For one, even though the GPU was ordered never breach the monitor’s limits, it had not been told to use the v-blank signal as the only basis for data requests. Thus there remained the chance, albeit a slimmer one, that a frame would be sent to the screen whilst a refresh cycle was in progress. Moreover, in circumstances where the host computer harboured exceptional pixels powers, such as when multiple GPUs were installed, input lag could still be an issue as soon as the card’s memory reserves were expended.

So Now What?

For many seasoned veterans, the choice was obvious and one which they shall steadfastly favour until an unconditional remedy materialises. I’d hoped to coin a phrase for it. Grindhouse Gaming. The term “Grindhouse” is most often associated with 1970s cinema and is american slang for a theatre that was used to screen content of an explicit and exploitative nature, produced on comparatively meagre budgets and due to poor quality prints, regularly exhibiting the visual equivalent of pops and clicks on vinyl record.

The genre was paid tribute by Quentien Tarantino in his 2007 film “Deathproof” and from a technical perspective, everyone of its defining details was clinically observed. Colour bleed, dust and scratches on the film, cigarette burns as the reels were changed. How is this relevant? Simple, just as there were audiophiles who were tied to their turntables and film buffs who would settle for nothing less than a human projectionist, there are gamers who would gleefully embrace a warts and all experience in order to extract their video card’s full potential. As we know, with vsync out of the picture, the GPU was not compelled to align its flips with the display’s vertical blanks and could liberally unleash every image it had rendered , thereby eliminating buffer overflow, maximising speed and minimizing latency.

Gsync and Freesync

Even when faced with an affliction that had undermined the lives of millions on both sides of the great graphical divide, our two ferocious foes found it impossible to cast aside their pipe sabres and and resolve it for sake of humanity. As I’ve laid out this article out in the form of a half-baked glossary with, there’s no opportunity to subtly segue into what might be the start of a perfect cure for all our torn hearts and shorn souls. Instead, I shall revisit a previous analogy one last time.

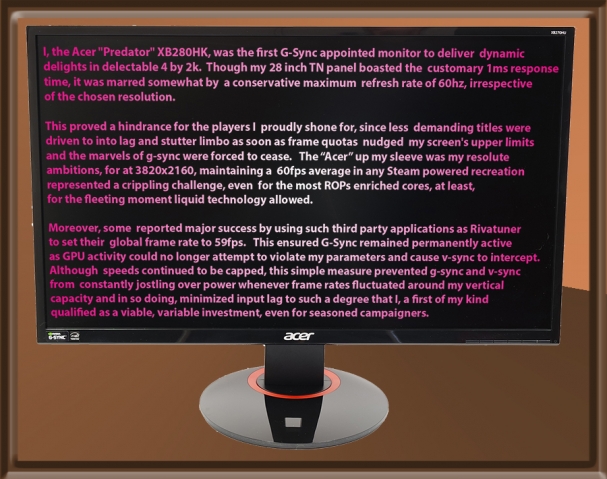

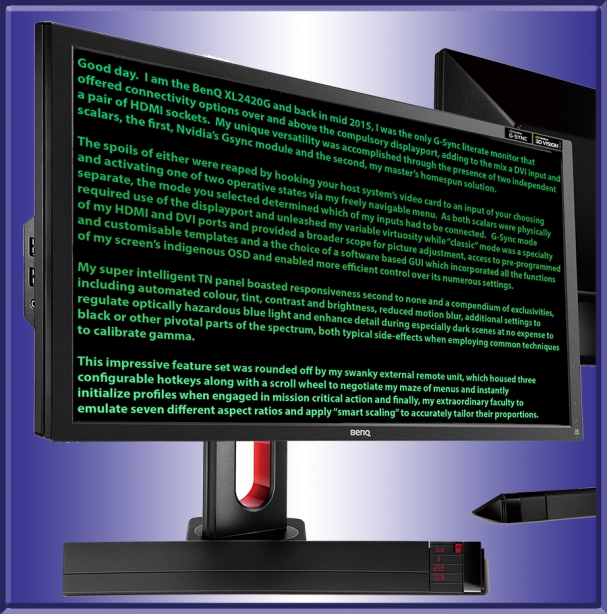

Gsync and Freesync are to a graphics card and its monitor what the good old fashioned land line was to two people trying to hold an intelligible conversation. The announcement of G-Sync in the winter of 2013 was met with cacophony of cynicism, principally because it demonstrated Giant Greeneyes’ propensity to profiteer by producing proprietary remedies to ailments as prevalent as….cooperate opportunism. His invention consisted of a custom module built into monitors whose vendor’s had paid for the hardware and sold separately for end user’s to install in compatible displays available prior, or subsequent to launch. I found one such product.

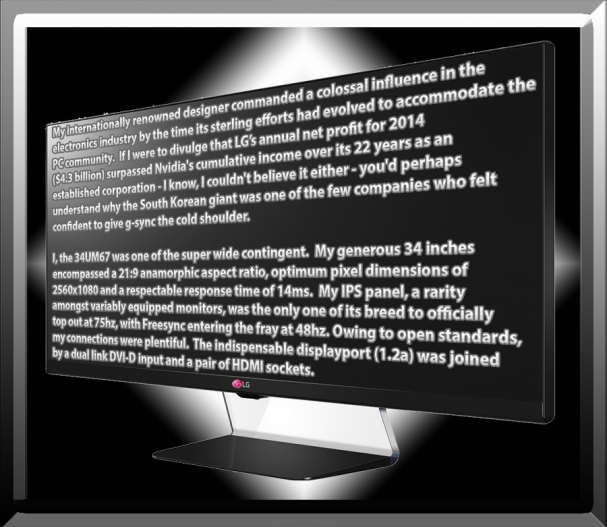

By contrast Redbeards response weaponized a specific aspect of the Displayport interface, adaptive sync, devised by VESA and in existence since 2009. Though an intrinsic part of the protocol from the point of its inception, this particular feature was not commercially implemented on conventional displays until 2014, when VESA elected to make it a native function of revision 1.2a and AMD announced their intentions to re-brand and market it as Freesync, a practical alternative to Gsync. Instead of relying on patented engineering, Freesync was theoretically available on any monitor armed with a displayport 1.2a connector, as support was programmed into the scaler, an indigenous component behind every panel. In securing endorsements from willing manufacturers, camp Scarlett was adamant it would obliterate Nvidia’s head start by achieving broader distribution and eventually provide an equally effective but far more accessible solution for consumers.

Displays that supported either standard boasted the facility to transmit dynamic refresh rates within a pre-specified range decreed by the manufacturer. For the initial wave of products, these “windows of opportunity” typically commenced at 30-40hz and topped out at 120 or 144hz. For any activity that fell within these accommodating boarders, the monitor was able vary its vertical frequency in increments of 1hz and in precise accordance with the GPU’s output. Hence, for the first time ever with VSync engaged, frame rates were explicitly governed by the graphics card, eluding all three encumbrances previously discussed and guaranteeing a glorious cocktail of creamy visuals, razor sharp responsiveness, suppressed lag and stifled stutter.

Whatever a loyalists preaching might claim, the differences between these two systems were more a matter of integration as opposed to efficiency and variance in quality in was difficult to detect. There were a however a couple of notable exceptions. With Freesync active, if the frame rate crept above the variable zone, AMD presented the choice of either reverting to traditional vsync to prevent tearing from returning, or forgoing it to bolster speed.

In the case of G-sync, Nvidia’s policy was to enforce standard v-sync whenever this perimeter was breached, on the assumption that any gamer who insisted higher frame averages, would likely be content to forfeit V sync entirely. Either that or they were confident their technology could triumph on quality alone and wanted to present it in the glossiest form imaginable regardless of their customers’ individual tastes. It sounds silly, but this theory is given credence when we consider what happened when frequencies violated their lower extremities.

Turning back to Freesync, as soon as the frame rate dipped under the monitor’s dynamic domain, the user was afforded exactly the same option, to enable or disable vanilla vsync. G-sync, in dramatic contrast worked by repeatedly increasing the display’s frequency in concurrence with the frame rate descending below several predetermined thresholds, whilst simultaneously inserting duplicate frames to artificially preserve smoothness.

The boundaries themselves varied from one screen to the next, but to take Acer’s XB270HU as an example, down to a value of 37, both the frame and redraw rates were symmetrical, though as soon as the former fell from 37 to 36 fps, the frequency would leap back up to 72hz and decrease in increments of 2hz for each frame lost thereafter. At 19fps, the frequency was again poised on its minimum of 37hz, and the instant this dropped to 18, the panel would recalibrate to 56hz and decline on a scale of 3hz per frame. 12fps would trigger 48hz, and so on down in progressively smaller ascents until frame rates reached rock bottom. At the moment of each transition, an additional cloned frame was interpolated so as to evade excessive flicker and force the master frames to disperse as evenly as possible throughout each second of rendering.

The technique was a curious and effective one and when considered alongside G-Sync’s behaviour at the display’s spectral maximum serves to substantiate the notion that Nvidia’s ultimate priority inclined toward artistic finesse and away from raw performance. It offered superior quality to AMD’s all or nothing alternative since it was the virtual equivalent of a variable V-Sync window with no lower limit. With Freesync, when frame rates hovered around the optimum zone’s minimum frequency, the aesthetic anomalies precipitated by V-Sync’s random and rapid interventions proved extremely distracting, whilst reverting to traditional v-sync resurrected the horrors of stutter and strife.

Some Parting Forecasts.

As frame addiction inevitably intensified, so too did wondrous windows widen. By early 2018, upper refresh rates had rocketed to over 200hz with proportionally rising prices, whilst during the interim period, AMD and numerous monitor vendors collaborated to initiate adaptive sync over HDMI, ensuring Freesync branded products offered a greater array of connections due to the standard having derived from VESA’s existing, universal specification and with no proprietorial appendages. Meanwhile, Nvidia decided that the display port was the sole interface they wished to utilise to implement and evolve G-Sync, though this didn’t prevent monitors certified for the standard from regularly incorporating HDMI’s latest incarnation.

As things stood in the spring of 2015, those susceptible to an emerald’s charms could not luxuriate in “near perfect synchronicity” unless their cherished Geforce cards were linked to a G-Sync monitor. As adaptive sync was an open standard, Old Green Eyes had the option to execute it in precisely the same fashion as his crimson nemesis and remove the necessity of his modular magician. Should Freesync prove especially popular, he may well be forced to do so and avoid alienating his comprehensive clientèle. Whether or not he would continue to promote and refine his personal innovation under such volatile circumstances, remained to be seen. For almost four of our native planet’s leisurely laps around the sun, legions of eye-candy converts were confounded by this conundrum, which was further aggravated by a perplexing choice of potent solutions from both sides of the great graphical divide.

Nvidia’s extortionate policy perpetuated despite a steady swell of scepticism, compounded by the emergence of several pivotal Freesync features, all of which served to significantly reduce G-Sync’s functional and optical superiority. At last, in an unforeseen and sensational twist during the biggest annual gathering of technological creators, coercers and consumers, the Verdant Goliath’s vivacious CEO Jensen Haung announced that Geoforce drivers would henceforth permit all G-Sync capable cards to showcase their flawless frame pacing through a Feesync display.

A momentous capitulation that aroused vivid memories of when Nvidia was effectively forced to retire its notorious NForce motherboard chip-sets and consequently, terminate a five year prohibition of SLI upon Intel’s competing solutions though by contrast, Nvidia’s present change of heart had not stemmed from legal toxicity and was instead construed by many as an unprecedented showing of progressive diplomacy. Yet, no corporate colossus worth its weight in smouldering pride would dare be seen to relinquish a hint of control over their market without cannily leveraging fresh commodities from such a sacrifice and true to form, clan green were as shrewd a Shark selling life insurance to its imminent prey. First, only cards bearing their recent Pascal and Turing chips were able to avail of the concession, leaving those whose older GPUs could still tear a high-def hole in any triple A title with no option but to abandon themselves to reckless profligacy.

Second, within the very same CES presentation, Nvidia unveiled a triple tier certification program.

The least prestigious class, “G-Sync compatible”, incorporated hundreds of “Freesync” branded monitors that Nvidia claimed to have rigorously auditioned to verify that they furnished prospective gamers with a premium “framing” experience bereft of flickering, drop-outs, artefacts and ghosting and moreover, provided a variable spectrum where the maximum refresh was at least 2.4 times greater than the minimum.

The precise methodology of this assessment was indistinct, though cynics were prompt to assert that it was Nvidia’s insurance against the potential redundancy of a formerly profitable selling point and that the criteria to procure these dubious seals of approval would be based on the “charitable generosity” of monitor vendors seeking to substantiate new products with a distinguished and lucrative accolade.

The second group, “G-Sync certified”, represented Nvidia’s effort to remedy its hardware’s declining lustre. It consisted of displays that both housed the notoriously extravagant FPGA chip and had transcended over 300 clandestine tests relating to image quality.

The company also explicitly restated several assets that had fortified its platform’s initial appeal and adaptive range with no minimum, colour calibration out of the box, dynamic overdrive to minimise motion blur covering the monitor’s entire refresh continued to ensure that, irrespective of the host panel’s credentials, the customer would acquire a technically optimal implementation of the underlying concept, a guarantee not available to Freesync customers until the Summer of 2018, when AMD introduced a more stringent set of parameters decreeing that all monitors worthy of “Freesync 2” classification must deliver HDR with a brightness of at least 400 nits, exceed a specific colour gamut and contrast ratio, generate a near negligible input lag and perhaps most crucially, support Low Frame-rate compensation, a veritable replica of Nvidia’s formerly unique “phantom image” scheme. To counter its ruby rival, the Jade Giant’s third and most exclusive category “G-Sync Ultimate” also stipulated HDR as a principal requirement to merit qualification but raised the applicable specifications to levels that only handful of prohibitively priced hyper-flagship displays embodied.

Elder readers might recognise that the above is a pictorial paraphrase of a vintage Two Ronnies Comedy Sketch intended to ridicule the absurdists of rampant classicism. One might have thought that over half a century of technological evolution would have involuntarily revealed a remedy to, instead, it has unearthed ever more radical methods to aggravate and monetise it.