Perfect Synchronicity.

Gsync and Freesync

Even when faced with an affliction that had undermined the lives of millions on both sides of the great graphical divide, our two ferocious foes found it impossible to cast aside their pipe sabres and and resolve it for sake of humanity. As I’ve laid out this article out in the form of a half-baked glossary with, there’s no opportunity to subtly segue into what might be the start of a perfect cure for all our torn hearts and shorn souls. Instead, I shall revisit a previous analogy one last time.

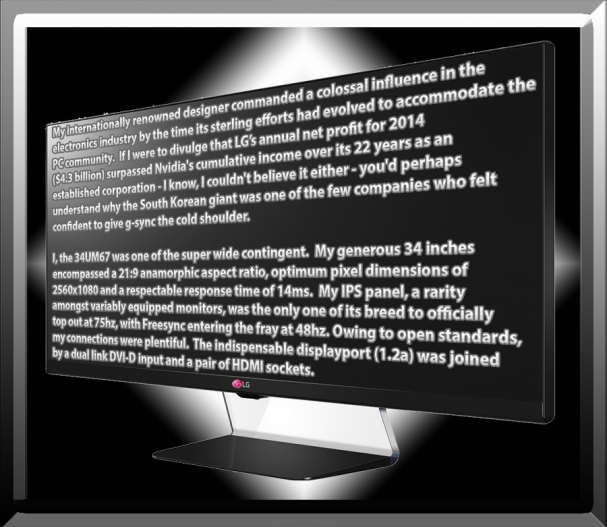

Gsync and Freesync are to a graphics card and its monitor what the good old fashioned land line was to two people trying to hold an intelligible conversation. The announcement of G-Sync in the winter of 2013 was met with cacophony of cynicism, principally because it demonstrated Giant Greeneyes’ propensity to profiteer by producing proprietary remedies to ailments as prevalent as….cooperate opportunism. His invention consisted of a custom module built into monitors whose vendor’s had paid for the hardware and sold separately for end user’s to install in compatible displays available prior, or subsequent to launch. I found one such product.

By contrast Redbeards response weaponized a specific aspect of the Displayport interface, adaptive sync, devised by VESA and in existence since 2009. Though an intrinsic part of the protocol from the point of its inception, this particular feature was not commercially implemented on conventional displays until 2014, when VESA elected to make it a native function of revision 1.2a and AMD announced their intentions to re-brand and market it as Freesync, a practical alternative to Gsync. Instead of relying on patented engineering, Freesync was theoretically available on any monitor armed with a displayport 1.2a connector, as support was programmed into the scaler, an indigenous component behind every panel. In securing endorsements from willing manufacturers, camp Scarlett was adamant it would obliterate Nvidia’s head start by achieving broader distribution and eventually provide an equally effective but far more accessible solution for consumers.

Displays that supported either standard boasted the facility to transmit dynamic refresh rates within a pre-specified range decreed by the manufacturer. For the initial wave of products, these “windows of opportunity” typically commenced at 30-40hz and topped out at 120 or 144hz. For any activity that fell within these accommodating boarders, the monitor was able vary its vertical frequency in increments of 1hz and in precise accordance with the GPU’s output. Hence, for the first time ever with VSync engaged, frame rates were explicitly governed by the graphics card, eluding all three encumbrances previously discussed and guaranteeing a glorious cocktail of creamy visuals, razor sharp responsiveness, suppressed lag and stifled stutter.

Whatever a loyalists preaching might claim, the differences between these two systems were more a matter of integration as opposed to efficiency and variance in quality in was difficult to detect. There were a however a couple of notable exceptions. With Freesync active, if the frame rate crept above the variable zone, AMD presented the choice of either reverting to traditional vsync to prevent tearing from returning, or forgoing it to bolster speed.

In the case of G-sync, Nvidia’s policy was to enforce standard v-sync whenever this perimeter was breached, on the assumption that any gamer who insisted higher frame averages, would likely be content to forfeit V sync entirely. Either that or they were confident their technology could triumph on quality alone and wanted to present it in the glossiest form imaginable regardless of their customers’ individual tastes. It sounds silly, but this theory is given credence when we consider what happened when frequencies violated their lower extremities.

Turning back to Freesync, as soon as the frame rate dipped under the monitor’s dynamic domain, the user was afforded exactly the same option, to enable or disable vanilla vsync. G-sync, in dramatic contrast worked by repeatedly increasing the display’s frequency in concurrence with the frame rate descending below several predetermined thresholds, whilst simultaneously inserting duplicate frames to artificially preserve smoothness.

The boundaries themselves varied from one screen to the next, but to take Acer’s XB270HU as an example, down to a value of 37, both the frame and redraw rates were symmetrical, though as soon as the former fell from 37 to 36 fps, the frequency would leap back up to 72hz and decrease in increments of 2hz for each frame lost thereafter. At 19fps, the frequency was again poised on its minimum of 37hz, and the instant this dropped to 18, the panel would recalibrate to 56hz and decline on a scale of 3hz per frame. 12fps would trigger 48hz, and so on down in progressively smaller ascents until frame rates reached rock bottom. At the moment of each transition, an additional cloned frame was interpolated so as to evade excessive flicker and force the master frames to disperse as evenly as possible throughout each second of rendering.

The technique was a curious and effective one and when considered alongside G-Sync’s behaviour at the display’s spectral maximum serves to substantiate the notion that Nvidia’s ultimate priority inclined toward artistic finesse and away from raw performance. It offered superior quality to AMD’s all or nothing alternative since it was the virtual equivalent of a variable V-Sync window with no lower limit. With Freesync, when frame rates hovered around the optimum zone’s minimum frequency, the aesthetic anomalies precipitated by V-Sync’s random and rapid interventions proved extremely distracting, whilst reverting to traditional v-sync resurrected the horrors of stutter and strife.

Some Parting Forecasts.

As frame addiction inevitably intensified, so too did wondrous windows widen. By early 2018, upper refresh rates had rocketed to over 200hz with proportionally rising prices, whilst during the interim period, AMD and numerous monitor vendors collaborated to initiate adaptive sync over HDMI, ensuring Freesync branded products offered a greater array of connections due to the standard having derived from VESA’s existing, universal specification and with no proprietorial appendages. Meanwhile, Nvidia decided that the display port was the sole interface they wished to utilise to implement and evolve G-Sync, though this didn’t prevent monitors certified for the standard from regularly incorporating HDMI’s latest incarnation.

As things stood in the spring of 2015, those susceptible to an emerald’s charms could not luxuriate in “near perfect synchronicity” unless their cherished Geforce cards were linked to a G-Sync monitor. As adaptive sync was an open standard, Old Green Eyes had the option to execute it in precisely the same fashion as his crimson nemesis and remove the necessity of his modular magician. Should Freesync prove especially popular, he may well be forced to do so and avoid alienating his comprehensive clientèle. Whether or not he would continue to promote and refine his personal innovation under such volatile circumstances, remained to be seen. For almost four of our native planet’s leisurely laps around the sun, legions of eye-candy converts were confounded by this conundrum, which was further aggravated by a perplexing choice of potent solutions from both sides of the great graphical divide.

Nvidia’s extortionate policy perpetuated despite a steady swell of scepticism, compounded by the emergence of several pivotal Freesync features, all of which served to significantly reduce G-Sync’s functional and optical superiority. At last, in an unforeseen and sensational twist during the biggest annual gathering of technological creators, coercers and consumers, the Verdant Goliath’s vivacious CEO Jensen Haung announced that Geoforce drivers would henceforth permit all G-Sync capable cards to showcase their flawless frame pacing through a Feesync display.

A momentous capitulation that aroused vivid memories of when Nvidia was effectively forced to retire its notorious NForce motherboard chip-sets and consequently, terminate a five year prohibition of SLI upon Intel’s competing solutions though by contrast, Nvidia’s present change of heart had not stemmed from legal toxicity and was instead construed by many as an unprecedented showing of progressive diplomacy. Yet, no corporate colossus worth its weight in smouldering pride would dare be seen to relinquish a hint of control over their market without cannily leveraging fresh commodities from such a sacrifice and true to form, clan green were as shrewd a Shark selling life insurance to its imminent prey. First, only cards bearing their recent Pascal and Turing chips were able to avail of the concession, leaving those whose older GPUs could still tear a high-def hole in any triple A title with no option but to abandon themselves to reckless profligacy.

Second, within the very same CES presentation, Nvidia unveiled a triple tier certification program.

The least prestigious class, “G-Sync compatible”, incorporated hundreds of “Freesync” branded monitors that Nvidia claimed to have rigorously auditioned to verify that they furnished prospective gamers with a premium “framing” experience bereft of flickering, drop-outs, artefacts and ghosting and moreover, provided a variable spectrum where the maximum refresh was at least 2.4 times greater than the minimum.

The precise methodology of this assessment was indistinct, though cynics were prompt to assert that it was Nvidia’s insurance against the potential redundancy of a formerly profitable selling point and that the criteria to procure these dubious seals of approval would be based on the “charitable generosity” of monitor vendors seeking to substantiate new products with a distinguished and lucrative accolade.

The second group, “G-Sync certified”, represented Nvidia’s effort to remedy its hardware’s declining lustre. It consisted of displays that both housed the notoriously extravagant FPGA chip and had transcended over 300 clandestine tests relating to image quality.

The company also explicitly restated several assets that had fortified its platform’s initial appeal and adaptive range with no minimum, colour calibration out of the box, dynamic overdrive to minimise motion blur covering the monitor’s entire refresh continued to ensure that, irrespective of the host panel’s credentials, the customer would acquire a technically optimal implementation of the underlying concept, a guarantee not available to Freesync customers until the Summer of 2018, when AMD introduced a more stringent set of parameters decreeing that all monitors worthy of “Freesync 2” classification must deliver HDR with a brightness of at least 400 nits, exceed a specific colour gamut and contrast ratio, generate a near negligible input lag and perhaps most crucially, support Low Frame-rate compensation, a veritable replica of Nvidia’s formerly unique “phantom image” scheme. To counter its ruby rival, the Jade Giant’s third and most exclusive category “G-Sync Ultimate” also stipulated HDR as a principal requirement to merit qualification but raised the applicable specifications to levels that only handful of prohibitively priced hyper-flagship displays embodied.

Elder readers might recognise that the above is a pictorial paraphrase of a vintage Two Ronnies Comedy Sketch intended to ridicule the absurdists of rampant classicism. One might have thought that over half a century of technological evolution would have involuntarily revealed a remedy to, instead, it has unearthed ever more radical methods to aggravate and monetise it.