Edirol SD-90

A Rare and Wrongfully Overlooked Harmonic Hybrid

Speaking as an emphatic champion of all non-digital memorabilia, or in the religious sense an “ardent analogue apologist”, it is with a tinge of guilt that I admit to an arsenal absent of a sole bona-fide binary free music box. Moreover, my most credited tune smith is not my most ancient, though it is probably the hardest to source.

Barely a handful of chromosomes away from the Sc-8850 in terms of cosmetics, the Edirol SD-90’s closest relative is likely its elder’s digitally endowed cousin and last in Roland’s sound canvas family, the SC-D70, while in the context of these four walls, it lies technically (and physically) sandwiched between the SC-8850 and Fantom XR.

Owners of this, the top ranked model in the company’s smallest “Studio Canvas” family, had at their disposal a complete and thoughtfully appointed music and audio delicatessen with no necessity to acquire a peripheral sound card for general use. The SD-90 did it all!

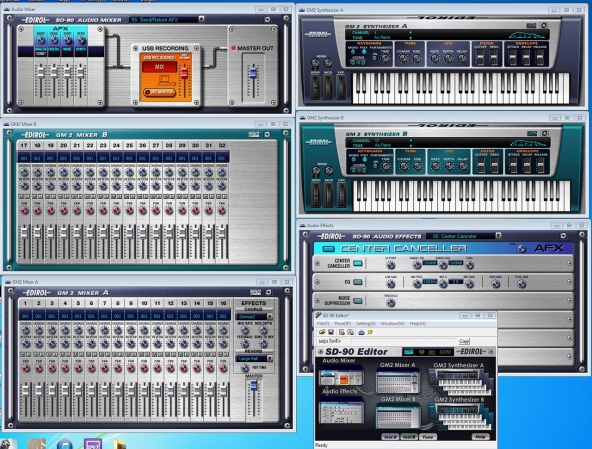

Its tonal assembly amounted to a respectable 1050, a little short of SC-8850’s record but with a duo of “special” banks harnessing a brace of the most authentic, full-bodied and finely crafted samples to be offered by any contemporary or subsequent alternatives. In another nod to its heritage, the machine’s generous 32 parts of timbral talent was evenly split into two blocks of 16, branded “A” and “B”, via which a polyphony of 128 voices could pursue plagel perfection.

One could record from four separate sources, the internal synthesiser, the wave output, and RCA phono or digital inputs located on the back of the case. Coax and optical variants of the latter were available, though only one at a time could be ascribed line-in duties. A fifth option allowed the quartet to be ensnared as a whole, with level of each channel regulated by either the SDs knobs and buttons or sliders on a cute graphical mixer.

The range of effects and freedom of their designation also left nothing to chance. Each source could be allocated one of eight colourful filters, then recorded either in solo or merged with a “dry” or “wet” mix of the remaining sources.

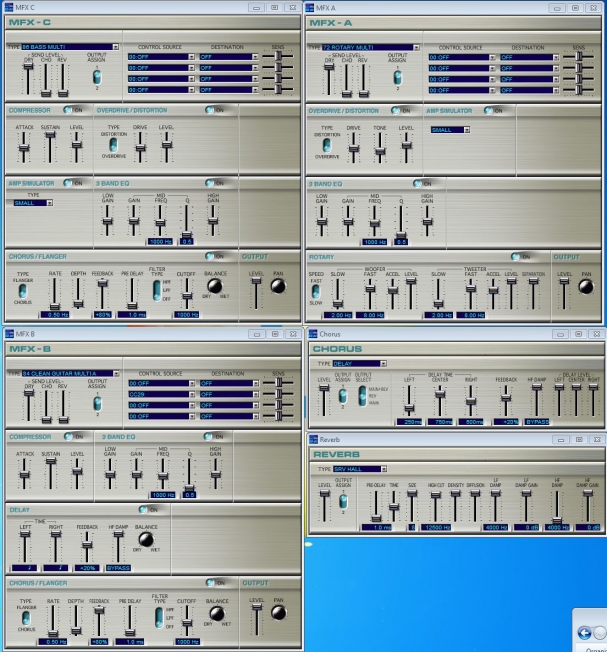

Like the Fantom, its engine room contained a triple helping of MFX turbines replete with an even broader medley of 90 intuitive pre-sets, while every one of the aforementioned’s defining elements such as pitch, frequency, phasing, resonance, EQ, delay, reverb and chorus could be regulated with an accuracy almost too extreme…just let your gimlet eyes digest those screen grabs.

Decidedly Fantomesque, but consider for a brief shining crotchet which came first….

A legacy USB cable and the appropriate “vendor” driver were all that the SD-90 sought to operate in splendid swing. Popular editing applications identified it as a solitary presence for recording and playback.

Assuming one used a keyboard to dictate its MIDI obligations, all imported and natively emitted audio could be fast tracked into the digital domain, mixed, mastered and distributed, bypassing the admittedly useful but voluntary complexities of a software sequencer, a party piece outside the realm of both the Fantom and sc-8850.

Once again, each FX processor was apt to artistically transform any or all of the SD-90s individual parts.

MIDI THRU Highs.

Both the SD-90’s MIDI outputs double up as “MIDI THRU” ports. With the unit in USB mode, one could connect a control surface to employ its innate and intriguing array of vocals, transmit any internally generated midi signals to either output, in addition to receive data from equipment tethered to either input, then either relay it to the corresponding output or reroute it to the alternate one.

Most exciting of all, if one could muster the patience to master an infernally irksome software tool, it was also possible to use a control surface to mix a palette of in house tonal wonders and to concurrently export the MIDI data to a second synth or sequencer. A somewhat expansive guide exploring enviable trick is available, its called MIDI through blues…but really I did get trifle carried away…and there’s the tiniest chance you’d be better off in consulting the manual.

MIDI THRU Blues Abridged Version.

When the SD90 is operating in USB mode and receives signals either directly through its MIDI inputs or via that of another USB device connected to the same computer such as an additional synthesiser, MIDI control surface or I/O adapter, either one of its MIDI outputs can be designated to re-transmit these signals to a connected device.

However, this is only possible when a program that fully utilizes the SD90’s USB driver and that of the other device – if applicable – is running. Prime examples would be sequencing software such as Sonar, Cubase and Logic, or the SD90’s proprietary editing tool.

If the option “MIDI IN THRU” is enabled on either of the unit’s inputs, the corresponding output will function as a standard MIDI THRU port and forward any received signals to connected hardware regardless of whether an application that employs its USB driver is open or not.

Both outputs can also be used to broadcast any signals originating from internal transmissions such as those generated when a MIDI recording is played back in one of the above programs on tracks to which the outputs have been allocated, or that occur when a MIDI file is opened up in utilities like QuickTime or Media player and either of the outputs has been specified as the OS’s default MIDI device.

Note that in both cases, it is the SD90s outputs and NOT its internal synth banks which must be selected and that as a result, unlike the Fantom or Integra, the SD90 is not able relay these signals to connected devices at the same time as emitting its own tones.

Edirol SD-90 – Brief tour of the Editor.

The SD shares the same patch, voice and tone naming fad as the Fantom XR, “tones” make up “patches”, thus, voices and tones to us are tones and patches to it, the remaining fundamentals do not alter.

The software supplied with the SD90 only acknowledged to the synthesiser’s GM2 sound banks and harboured no timbrel tailoring facilities. To gain access to its rich and radical repertoire of native tonality, it was necessary to use the editing application primarily attributed to its spiritual and physical half brother, the SD80.

Fortuntely, the ROMS under their respective roofs were identical, with the SD90’s only enhancement being its aptitude to serve as a conventional sound card and combine its virtuous vocals with a collection of digital effects.

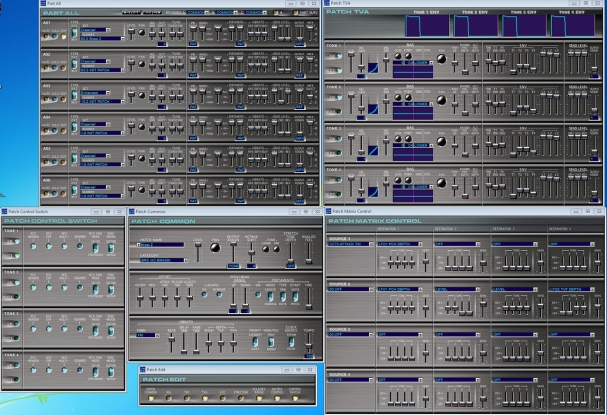

At first glance, the program reveals a very similar GUI to that of the Fantom XR and despite not featuring separate Performance and Patch modes, all of its comprising patches (tones) can be edited and refined on a tone (voice) specific basis in exactly the same fashion.

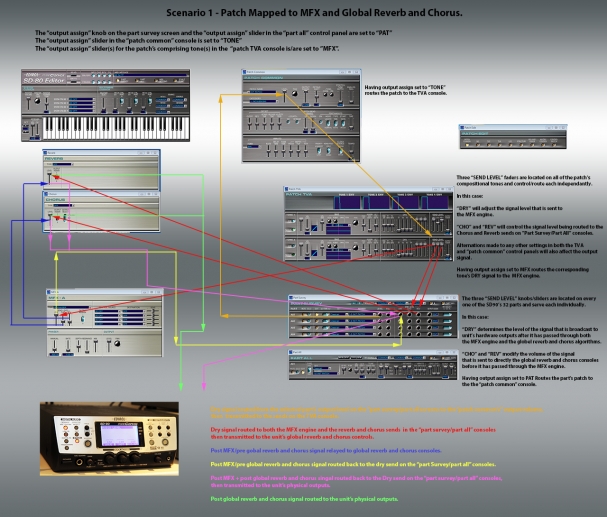

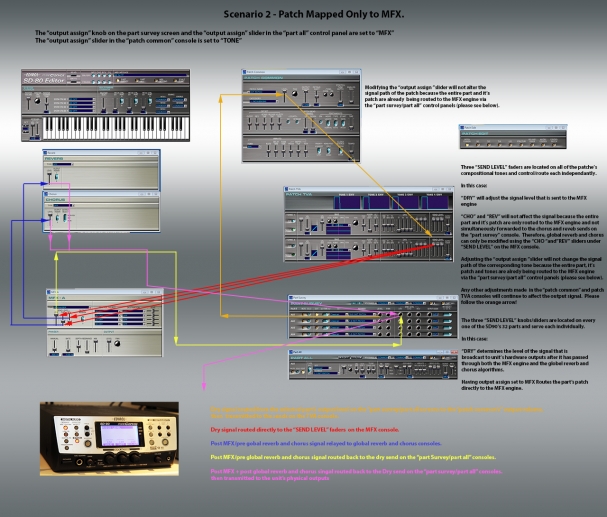

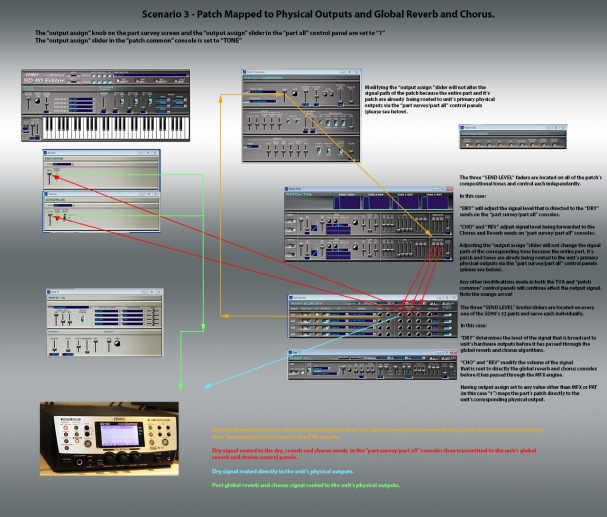

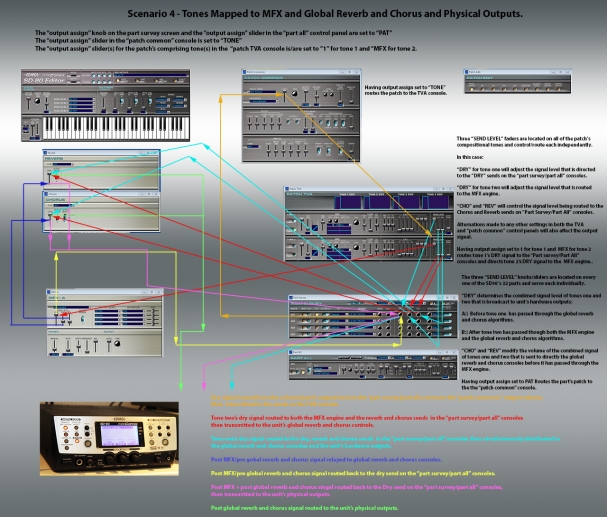

As soon as the initial screen appears, clicking on the “part survey” button will call up a crucial control panel presenting an overview of the fundamental settings applicable to each part, including its prescribed patch, settings for reverb chorus and delay, output assign and a switch to direct the patch through one of the unit’s three multi FX engines (A, B or C).

The “output assign” knob is crucial and controls where the part and its applicable patch is being routed.

A single click on the “Edit” button of any part will activate the “Patch Edit” strip for that part and it’s initialized patch, from which all the settings pertaining to the patch and the tones it is compiled from can be accessed.

One click on the button inscribed “Patch TVA” will initiate the “Patch TVA” console where detailed settings specific to the patch’s compositional tones can be customised. The TFA and LFO consoles also apply here, though as with the Fantom, the TVA fosters additional faders for dry signal, reverb and chorus sends and “output assign” allocated to each of the patch’s underlying tones. As the SD-90’s editor has no “FX routing” screen, this is of as it is the only way to route a patches separate elements either directly to an output or to one via the MFX engine.

Pressing the “Patch Common” button will bring up the “Patch Common” control panel.

This also has a slider entitled “output assign” which is used to determine the ultimate destination of the patch (tone) and the tones (voices) that it encompasses.

When set to “Tone”, the patch or played sound is referred to the “patch TVA” console.

When the slider set to MFX, the entire patch is mapped directly to the multi effect selected for that part on the “part survey” console (either A, B or C) which can then be combined with the unit’s communal chorus and reverb effects via the applicable MFX console .

When set to any other value (1, 2, 1r, 1l, 2r, 2l) the patch/audio signal bypasses the MFX engine and is transmitted directly to the unit’s physical outputs.

Parameters relating to the selected multi effect MUST initially be dictated using their respective control panels. Once again, these are accessed on the applications main screen by clicking the blue buttons next to “param”and under “mfx” and rev”

Similarly, granularity, type and texture of reverb and chorus must first be defined in the global reverb and chorus consoles. These are accessed on the applications main screen – the one with the virtual keyboard – by clicking the blue buttons next to “param” and under “cho” and rev”.

The “part survey screen” together with the “part all” screen on the sd-90 should be treated the same way as the “fx routing” control panel on the Fantom XR.

For example, on the part survey screen, when the dial under “output assign” for any part is set to a value other than “PAT” (patch) the “output assign” faders in both the “Patch TVA” console AND the “Patch Common” control panel are bypassed as the entire patch and hence, its full mix of voices are being mapped either directly to an output, or to one via the MFX processor.

Moreover, if the dial is set to “MFX”, the knobs/sliders for “chorus” and “reverb” on the “part all” and “part survey” screens no longer affect the output signal.

These diagrams are intended to illustrate the signal path(s) that a patch will be assigned when applying four different combinations of settings.

Only one of the three MFX engines (A B or C) can be applied to a particular part, though all three can serve alternate parts concurrently.

Contrary to the Fantom, it would appear the SD90 only possesses the facility to route patches (tones) and tones (voices) either directly to its primary physical outputs as two channel signal and/or to them via the MFX processor. It cannot allocate patches or individual tones to its secondary outputs or to specific left or right channels its primary outputs, despite the relevant controls being provided.

Pages: 1 2