German company RME has, for almost a decade, been revered in the audio engineering industry for designing and producing some of the most reliable, versatile and – many would claim in view of their class leading performance and build quality – affordable components available to the professionally minded user, let’s leave out such terms as “semi-pro” and “pro” when the former so gracefully accommodates both!

Aside from technical excellence, RME’s products, from the very outset, offered full compatibility with a comprehensive range of third party applications, thereby representing a perfect and consistent alternative to, for example, a long term Adobe Audition user such as myself, who might otherwise have been forced to invest even more in an “industry standard” Pro-Tools based setup.

Since Avid Audio’s acquisition of Digidesign at the end of 2010 and the subsequent release of Pro-Tools 9, Pro-tools no longer requires its parent company’s proprietary hardware in order to function hence, one’s weapon of choice is far less of a dilemma .

With this in mind, it could hardly be a more fitting time to examine one of RME’s latest works of art, the crown jewel amid their current range of external interfaces, the Fireface UFX.

Once upon a time, centuries ago….in 2004, RME conceived and created its venerable Fireface 800, a revolutionary product whose high quality preamps, reference level A/D D/A converters and ingeniously designed drivers, promptly defined a spectacular new standard for firewire-based audio capture.

Though it was generally assumed that the UFX would be the 800’s fervently anticipated successor, RME has demonstrated another of its rare and admirable traits as a company, loyalty to the long-term user. They are adamant that their new unit shall in no way be treated as a direct replacement and have pledged full, ongoing driver development and technical assistance to all owners of either or both…who says there’s only room at the top for one?!

So what of this fresh and delectable sonic marvel?

As with the Fireface 800, the UFX’s gamut of features is conveniently contained within a traditional 1U rack mountable chassis, the dimensions of which are identical to its elder sibling.

Zooming in on the front left, we can observe four balanced microphone inputs. Each benefits from a dedicated, digitally controlled, high-transparency preamp, adjustable over a range of 65db and based on the same core technology as those found in RME’s eight channel “Micstacy”, a significant step-up from the 800. These preamps hand duty over to 8 A/D converters – two assigned to each preamp – which work in parallel to deliver an exceptionally high signal-to-noise ratio of 115dbs(a). Moreover, unlike the traditional XLR sockets of the 800, these are combo connectors, doubling up as 1/4 inch unbalanced line-level and Hi-Z instrument inputs.

Note the three lights next to each socket. When the UFX is powered up, the top-most (marked “sig”) indicates the presence of an audio signal passing through the corresponding input, the middle (48v) denotes whether “phantom” power is being supplied from the input (essential for condenser microphones) and the last (TRS) indicates whether or not the 1/4 inch “instrument” input is active for each socket. Both phantom power and TRS mode are activated via “TotalMix”, RME’s fantastically intuitive software control panel which we will examine later.

To the right of the mic inputs, we find a pair of 1/4 inch stereo headphone sockets which as shown, have been allocated four of the UFX’s 12 analogue outputs (channels 9 through 12). Next to these is a MIDI I/O terminal, allowing the UFX to be operated by an external MIDI controller such as the Mackie MCU Pro, as well as transmit and receive to and from any other MIDI device. Lastly, we have a USB port to which a flash drive can be connected, enabling the UFX to function as a versatile, self-contained solid state recorder during live concerts and fieldwork.

Panning along to the right reveals a cluster of LEDs denoting the operating mode of the unit (Firewire or USB), the sync status of the word clock, AES and ADAT inputs and any MIDI activity. Next to these, we have the master volume control, which adjusts the UFX’s main outputs in addition to both headphone outputs.

Alongside are four buttons which, in tandem with their neighboring high-res LCD and the two knobs beside it, can be used to control all of the UFXs functions, including its FX and dynamics processors, independently of a computer. Finally…ah yes….a fully serviceable on off switch!

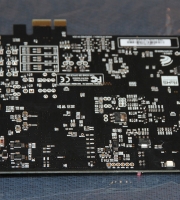

A quick trip around the back of the unit and, next to the AC power input on the left, we discover a second MIDI I/O terminal, a firewire 400 and usb 2.0 port, the latter which RME claim to be fully compatible with USB 3.0 chipsets (though there is no benefit in performance). Immediately above is a remote interface that supports one of RME’s two proprietary remote control units, the “basic” and the “advanced”. These can be used to toggle and adjust specific functions of the UFX such as volume, mute and solo, talk-back and cue the headphone mixes to the main outputs. It is important to mention these are only the default values and if required, the user can reassign the buttons and dial to control any one of around forty additional functions, this as ever, is achieved via the TotalMix console.

Immediately to the right of the remote socket is the unit’s Word Clock I/O for those who wish to connect an external master Word Clock module such as Apogee’s “Big Ben” to the UFX, or use the UFX’s own ultra low jitter internal clock as the master to drive another device. A 75 ohm termination switch is situated next to the input.

Just beneath, we have a pair of ADAT I/Os for those who, either have an old ADAT tape deck they have grown spiritually attached to or, more likely and dare I say, constructively, wish to increase their quota of inputs and outputs by way of an external AD/DA converter such as RME’s own ADI-8QS or Beringer’s far cheaper but still worthy Ultragain Pro-8. An important point for all intending to offload their old interface in favor a UFX, assuming it too has an ADAT I/O, why not hold on to, say, that Fireface 800…and have it serve as your UFX’s wise wing man instead?

The second ADAT ter’minal conveniently doubles up as a standard Optical SpDif interface, ideal for hooking up to the i/o of another soundcard or the output of an external synth, CD or Blu-ray player.

Moving across to the right rear reveals a third digital I/O, this time a professional AES/EBU interface which, along with the unit’s ADAT and analogue I/Os, supports sample rates of up to 192khz. Using an XLR (male or female) to phono adaptor or cable, allows both these connectors to function as a standard SpDif I/O.

Six 1/4 inch balanced outputs nestle to the right and alongside these, two balanced XLR outputs, the latter are defined as the UF’X’s main outputs and generate a level of up to +24dbu, ensuring the cleanest possible signal is sent to your studio monitors. Eight further 1/4 inch balanced sockets form the UFXs full complement of twelve analogue inputs.

Every one of the UFX’s digital and analogue I/Os, amounting to 60 channels in total, can be used simultaneously at sample rates of 44.1/48/88/96/176.4 and 192khz, though when operating at sample rates above 48khz, the number of ADAT channels is reduced in accordance with the table below:

And here, the UFX sits merrily atop of it’s elder. In comparing the two, we can see that RME has chosen to eliminate the manual gains beside each Mic input on the UFX, whose input levels are now digitally adjusted using either the TotalMix software or master control knob.

Looking at the back of both units, aside from the discrepancies in socket layout, the UFX’s XLR type master outputs and AES/EBU digital I/O are notable upgrades though the option to add RME’s Time Code module (TCO) was and remains exclusive to the Fireface 800.

Having marveled so extensively at the hardware and aesthetics, let’s now turn our attention to RME’s no less redoubtable software and drivers.

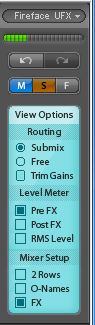

The TotalMix user interface has represented the skeleton key to the acoustic treasures within RME’s creations from the very beginning. Anybody savoring it for the first time could be forgiven for feeling daunted, even a little frustrated by the somewhat unconventional design. But those who persevere are bound to conclude that it is as effective in achieving sound success as the hardware it controls. The multitude of innovative and practical features it harnesses are best conveyed in the UFX’s substantial 110 page manual, nevertheless, here are a few of the basics.

In examining a full view of the console (please click the image to enlarge), we can see there are three rows of faders and VU meters.

The top most of these, labeled “hardware inputs”, corresponds to audio that is routed into the UFX from external devices. The most important aspect to remember is that the faders on this row do not, as one might assume, adjust the level of the signal being received by the inputs, which instead, is set at one of three available reference levels, -10DBv, +4DBu or lo gain, the latter intended for professional equipment that is capable of the loudest output.

The four mic inputs (9, 10, 11 and 12), have additional controls for preamp gain – up to a maximum of 65db in 1db increments – phantom power and instrument/Hi-Z mode (the buttons marked 48v and “Inst”). If the “Autoset” button is pressed, the gain is continually reduced in accordance with the loudest signals so as to prevent distortion automatically, a handy function for live events or field work where setup time may be scarce.

So, what do the faders do? They control the level of the audio that is being sent (routed) to the UFX’s outputs. In the example shown above (far left), we are looking at inputs 1 and 2 (as indicated by “AN 1/2” at the top, just above the pan control knob). Underneath the fader “AN 1/2” is displayed again, though this time, it represents the outputs to which the audio is being routed, in our case 1 and 2. Thus, dragging the fader up will allow the signal that is being received by inputs 1 and 2 to be routed to outputs 1 and 2, with the fader controlling the level of the routed signal, not the input.

A similar rule applies to the second row of faders and VUs, which represent the UFX’s software playback channels. These faders determine the level at which the sound is played back, but that sound will only be audible through the output(s) to which it is being routed. In the above example (middle left), audio that is being played back on channels 1 and 2 (as denoted again by “AN 1/2” at the top) will be routed to outputs 1 and 2 (“AN 1/2” at the bottom), with the fader once more defining the volume of the routed signal. The third and final row of faders, labeled “hardware outputs”, is where all sound routed from the hardware inputs and software playback channels is directed. In the above example (middle right), the fader will adjust the volume of any audio that is being routed out of the UFX via outputs 3 and 4 (labeled “AN 3/4” in the console).

Once the user is able to commit these simple principals to memory, unlocking and exploiting TotalMix’s wealth of options quickly becomes a logical and greatly enjoyable process.

Depending on the software you’re using – be it Audition, Pro Tools, Logic or other – the UFX’s inputs and software playback channels should both be detected as thirty individual Mono channels and/or fifteen stereo pairs. In the case of older applications which do not support ASIO, RME’s WDM compatible drivers ensure that virtually no functionality is lost. For example, in Adobe Audition 1.5, all fifteen stereo pairs for inputs and playback are still recognized, affording the option to select and record either the left or right channel of each whilst playback can occur on upto fifteen “wave out” devices at the same time. The drivers also support multi-client operation, meaning the user can run several audio capture applications simultaneously and assign different inputs and playback channels to each, just as versatile as having fifteen high quality sound cards installed at once, only far more practical!

Two of the most useful features introduced by the UFX are its built-in 3 band graphic equalizer and dynamics processor, both of which can be engaged on each and every one of the unit’s 30 inputs and outputs with the added convenience of numerous factory and user definable presets. Also very much worthy of note is the “loopback” button which, when activated, internally sends all audio routed to that output back to its corresponding “hardware input”, thus allowing a post FX, dynamics and EQ signal to be recorded without leaving the digital domain.

The UFX’s built-in FX generator allows for Reverb and/or Echo to be “sent” from any input or playback channel and “returned” to any output. A mini fader and rotary knob situated beside every channel is used to adjust the sends and returns. Unlike the EQ and dynamics processor, there it is not the option to apply different presets or algorhythms to specific channels. One cannot, for instance, have the “room 3” algorhythm active on channels 1/2 and the “classic” algorhythm on channels 3/4, it would need to be either “room 3” or “classic” for all four of these and every other channel, leaving the user only able to determine a “wetter or dryer” signal. Given that the FX processor offers a decent range of configurable settings, this is a little disappointing, but a deal breaker? I think not.

The UFX’s built-in FX generator allows for Reverb and/or Echo to be “sent” from any input or playback channel and “returned” to any output. A mini fader and rotary knob situated beside every channel is used to adjust the sends and returns. Unlike the EQ and dynamics processor, there it is not the option to apply different presets or algorhythms to specific channels. One cannot, for instance, have the “room 3” algorhythm active on channels 1/2 and the “classic” algorhythm on channels 3/4, it would need to be either “room 3” or “classic” for all four of these and every other channel, leaving the user only able to determine a “wetter or dryer” signal. Given that the FX processor offers a decent range of configurable settings, this is a little disappointing, but a deal breaker? I think not.

The “control room” is a special section located at the bottom right of the console where the user can allocate specific physical outputs to monitor playback. Each of these automatically becomes a fixed stereo output and accounts for two of the UFX’s thirty output channels . By default, outputs 9/10 and 11/12 (the two 1/4″ sockets on the front of the UFX) are reserved for use with headphones while outputs 1 and 2 (the XLRs on the back of the unit) are designated to carry the main mix. Two further headphone outputs can be assigned to the control room, along with a secondary master out, defined as “speaker B”.

Rounding off Totalmix, from left to right, we have a section containing additional settings regarding the console’s appearance and behavior. This includes global mute and solo buttons and DSP load meter (the partially green bar at the top), which indicates the proportion of the DSPs resources that is currently occupied by the internal EQ, dynamics and FX processors. Next is the SSD recorder’s control panel, which allows for the recording, navigation and playback of audio on a connected USB drive and finally, a place to quickly store and recall presets or “snapshots” of up to eight different TotalMix states, in other words, every setting on the console is committed to memory and instantly recalled when each “snapshot” is selected. The user can also save snapshots as separate files and store all eight current snapshots in a special “workspace” file, thereby allowing as many presets as your hard drive can accommodate!

Without access to an equivalent rival product, a constructive comparison isn’t possible, hence I cannot state definitively that the UFX is without peer. The Apogee Symphomy, Orpheous Sound Prism and Motu’s 828mk3 Hybrid have all been mentioned as viable alternatives but I’d raise an eyebrow at the audiophile who, following blind test, insisted that any was a clear cut above the RME’s solution.

Marrying it up with my trio of dynamic mics (two Heil PR40s and an Electrovoice Re27) served as indisputable proof of the preamps’ exemplary quality. Dynamic mics are generally known to require a higher gain from the preamp than condensers, though even when set at 60db, the sound remained smooth, clean and perfectly balanced, with no discernible characteristics other than those exhibited by the mics natural frequency response, in other words, as transparent as Lucifer’s conscience!

The remaning analogue and digital ins and outs all performed to spec under testing. With no equipment connected, noise floors measured between -109 and 110db (RMS unweighted) for the balanced inputs and -112db for the mic/instrument inputs. The digital inputs also functioned without issue. I used an XLR to coax adapter to hook up my Soundcraft M12 mixer, which emits a fixed sample rate of 44.1khz. This was duly detected by the UFX, which automatically entered slave mode and switched its clock source from “internal” to “AES”. No pops or clicks were evident on any recordings. Performance in Audition 3.0 and Cakewalk Sonar X1, my two most frequently used applications, was superb. Recording and playback were stable and extremely responsive. Even when multi-tracking with a gamut of FX and plugins, I rarely had to set the latency buffer above 256 samples.

In terms of performance, neither the built-in dynamics or FX processors are going to rival class leading, dedicated solutions such as are offered by TC electronics, but those who want nothing more than a simple compressor/expander along with convincing reverb and echo, will likely be satisfied by the UFX’s in house offerings and prefer not to sacrifice extra cash or valuable studio real state on outboard alternatives. Furthermore, the 3 band EQ more than matched the quality and versatility of that on my Soundcraft M12 mixer and with an armory of presets only a couple of clicks away, also eliminated a good deal of pre-session knob twiddling! It’s also worth emphasizing the that fact that all three of these features, the EQ, dynamics and FX processors, are integrated, since this allows for each to be applied exclusively within the UFX’s digital domain, resulting in optimum quality and negligible latency.

As a customer who purchased the UFX to replace a four year old Fireface 800, and one that had proven infallible throughout its service, I can without hesitation state that the transition has been as seamless and rewarding as I could possibly have wished and I’m almost certain that in another four years, the only thing likely to prevent me from indulging in RME’s next slice of sonic heaven, will be a bank statement.