As we approached the summer of 2014, any amount of heat generated by the most intense sun in a galaxy yet to be graced by NASA sleuths could surely have never equalled, let alone surpassed that brought about by the silicon soldiers, adorned in amour of gleaming crimson and blinding verdant, and their relentless struggle for pixel conjuring perfection.

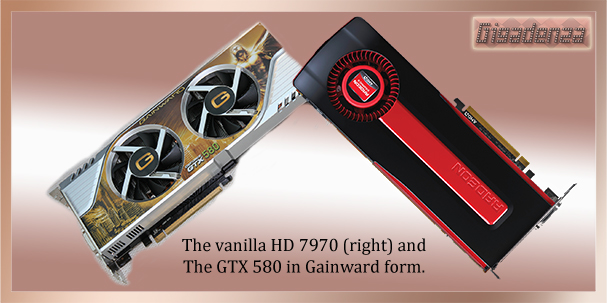

This particular phase of the battle arguably began over two years earlier, when, in Janurary 2012, AMD made the bold decision to release what was the world’s first 28nm GPU. The chip, codenamed “Thaiti” formed the basis of an exceptionally brisk family of video cards, the flagship being the HD 7970.

As was expected, its performance demonstrated marked improvements over Nvidia’s then finest, the GTX 580, a card which had impressively retained the single GPU crown throughout 2011.

Two months later, Giant Green eyes finally decided that it was time to respond, and unleashed a clutch of his own treasures, the GTX 680 being the crown jewel. The 28mn “Kepler” chip, which beat at its heart defined a new era of energy efficiency amidst high end graphical sorcery, one area in which Nvidia’s previous two generations of single GPU solutions had floundered. I am careful to again mention “single GPU” since in this somewhat retrospective take on resolution warfare it is especially important to distinguish between what is the fastest card housing just one GPU and what is the fastest card overall, for historically the latter is, almost without exception, a beast which plays host to twins.

The striving for dual GPU supremacy is similarly relentless, and the conundrum of raw performance at the cost heat, noise and eco friendliness even more difficult for both companies to master. As we observed a few chapters ago, their dual GPU offerings, though constructed around the same chips, were habitually hobbled by lower core and memory frequencies. A simple and effective solution to the risks of doubling up on an already power hungry design. This, combined with other small refinements to the manufacturing process, explains why it is dual GPU cards routinely emerge significantly later than their single GPU counterparts.

At such a point in the narrative, it is necessary to consult some tables documenting every officially released single and dual GPU flagship creation originating from messers Green and Red over the last 4 years.

First…we have AMD…

And now…Nvidia…!

Yes, I know, squint you might well , especially in the latter instance. I could of coarse have used a fancy plugin to allow any keen reader to click the images and have them willingly expand to managable proportions, though to do so would in itself hinder my conveying the potential difficulty for the customer to stay sane in the face of such profligate technological ping-pong.  Moving back to our timeline, I shall attempt to do so whilst observing as many specs and features worthy of mention, or as my mind can comfortably conceive.

With the release of the GTX 680, Nvidia had indeed gained an advantage in the mission for mono GPU stardom, though its lead was hardly unassailable.  AMD’s 7970 boasted 1GB of extra memory and a fatter bus, numbering 384bits upon which to transport it, this, combined with a more attractive price and rapidly evolving drivers, ensured its continued popularity. The 680 however, had party pieces of its own, the first, its own take on AMD’s “powertune” system, whereby the GPU’s speed and voltage  is finely optimised in accordance with the card’s maximum power consumption. In the case of the 680, Nvidia guaranteed a minimum speed at which its GPU would operate irrespective of workload, before going on to confidently predict the likelihood of a 5% (or 58mhz) bonus for the majority of the end-user’s requirements.

This brings us nicely onto another notable improvement, the card’s power limit, a mere 195 watts, 55 less than the 7970. Less power proved to be cooler and quieter, attracting numerous users planning a multi-card setup or high performance build in smaller case. The fact that a lower transistor count, a smaller die, inferior memory bandwidth and considerably fewer shader processors did nothing to prevent the 680 from surmounting the competition was not just a testament to its efficient design but also a sign that Nvidia had a copious quota of stops left to pull.  What’s that? How many GFlops? What about the texture rate?  I told you I’d refer to what was worthy in the context of the narrative, please consult the tables for the rest, its all there, I promise!

On the Dual GPU front, things were extremely close. Â The older 40nm process had initially represented something of a disaster for Nvidia. Â The GF110, or “Fermi” chip was ridiculed for its gluttonous power demands and even though these had been partially curtailed by the time the GTX 580 saw light, the company decided to become more conservative when assembling its dual GPU equivalent, the GTX 590.

The GPUs core speeds were dialed down from 772mhz to just 608, while memory was also restrained by effectively over 0.5ghz. Â Meanwhile, on the red team, AMD’s own 40nm top dog, the “Cayman”, which had piloted the HD 6970, had proven slower in singles competition but a touch less taxing on the national grid, resulting in a far more bullish approach for the double encore. 7

Indeed, the HD 6990 was the closest we had yet come (save for unofficial efforts by vendors such as Asus) to savouring  two fully unencumbered flagship GPU’s sharing the same PCB.  Stock core speed was cut by just 50mhz, while the user was invited to take liberties by activating a secondary BIOS via a physical switch on the card’s backplate, which raised the voltage of each GPU and utterly nullified this reduction, albeit at the expense of watts.

The 590 retained the advantages of  a wider memory bus and higher tally of Render Processors, while the 6990’s additional memory, texture units and superior floating point performance ensured an inevitable outcome…two monolithic frame rate virtuosos harvesting equal plaudits for benchmarks with a similar thirst for fuel, though as summer drew near in 2012, both had already reached the ripe old age of 1 and Nvidia, brimming with confidence in the wake of its recent singles victory, was about to try and unify the titles.  Excuse me?  What about the pixel rate, GFlops again??  Have you forgotten the tables already?? Everything I didn’t mention is right there….honestly.

In May, we were introduced  to the GTX 680’s twin headed brother, the GTX 690, whose pair of “Keplers”, owing to the new GPU’s supreme efficiency, were allowed to operate at virtually their original speed as well as benefit from the same “boost clock” feature.

Though the card’s exorbitant launch price was hard even for Nvidia’s fans to justify, two big green feet were now planted firmly in the 28nm era and if raw performance was all that mattered to their owner, he could rest easy….that is until June, when the term “pulling a fast one” could have scarcely been more apt to describe Giant Red Beard’s next attack on the singles front. Enter the HD 7970 “Ghz edition”, a supercharged version of its predecessor, same GPU, same quota of memory, same everything in fact, just a little faster.

DDR5 now zipped along at 6ghz, matching the 680s while core speed was cranked upto to 1ghz, with AMD implementing a somewhat cruder form of Nvidia’s “boost clock” by providing users with a fixed 50mhz bonus as permitted by the card’s power limit. Unoriginal, perhaps and any chance of praise from conservationists had, for now, been conceded to pastures green. Nevertheless, in the world of refresh rates, timedemos and bar charts, the move was enough for AMD to once again edge ahead.

One crown a piece, AMD, the singles champion by a hare’s breadth with both it and the 680 burning similarly sized holes in purchasers pockets. Nvidia, current leader in doubles but with a worfully pricey solution and AMD yet to offer a 28nm alternative.

In February 2013, following over six months of radio silence, it was Nvidia’s turn to be a little lazy and also the turn of the tortured sole that is the author of this article, after all, there are only so many flowery similes and metaphors one can employ to convey the capacity and fortitude of pieces of silicon. Â Let hard facts be my forte for the next few chapters.

In turning its attention to reclaiming singles dominance, the chip which Nvidia elected to exploit next was the GK110, which had made its début in the professional market four months earlier.  The design was barely distinguishable from that of GK104, in essence because it was the same “Kepler” GPU but with six additional Streaming Multiprocessors, each playing host to 64 double precision cores (useful for complicated research and rendering etc), to this was married a staggering 6GB portion of DDR5, three times as was allotted to the GTX 680, while the bus on which it travelled expanded from 256 to 384bits.  A more sophisticated form of “boost clock” was established, this time based on maximum temperature as well as power limits.  Core speed was a little slower, ostensibly to improve yield rates in light of the extra streaming processors, though memory frequency matched that of the 680…all this within the confines of 250 watts.

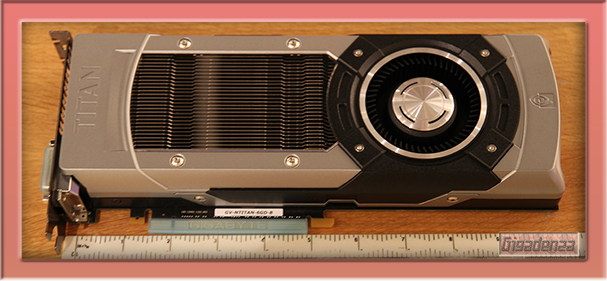

Gigabyte’s interpretation of the GTX Titan card (another reference design!)Â

For a modest £830, the keen enthusiast could acquire what Nvidia had christened the “GTX Titan”. Many claimed that this was an experiment by green team to see how many rich “consumers” could be tempted by the exclusivity of a “professional” product, whilst AMD’s fans were quick to point out that though the Titan convincingly displaced 7970 “GHz edition” at the top of the singles tree, a pair of 7970’s could be purchased for virtually the same price and generate superior performance in crossfire.

Such arguments might well have influenced AMDs response.  Their monumental HD 7990 officially emerged in April and presented us with two fully unlocked Thaiti’s screeching along at up to 1ghz, each sharing a Titan equalling 6GB of RAM.  Price was the same as the Titan, though more importantly, it also reflected that of the dual GPU card against which it was directly competing, Nvidia’s now year old GTX 690. Â

As anticipated, its performance was very close to the latter’s.  Some reviews gave it the overall edge, though others criticised its ludicrous lust for watts and observed that while benchmark figures were impressive, the age old Multi-GPU issue of micro-stutter was especially pronounced and would greatly tarnish any game player’s experience.  A prompt driver update proved sufficient to satisfy the majority.

A month or so later, Nvidia decided it was time to establish a sterner grip on its coveted singles belt and delivered card that many felt could and should have materialised before the prohibitively extravagant Titan.  Enter the GTX 780 a In short…two less streaming processors…a slightly quicker core…no double precision units…half the memory but almost half the price.  Despite the defecits, this “Titan Lite” yielded precious little frames to its elder and was again superior to the 7970 GHz edition.

Ardent AMDers continued to grumble over the green teams’ pricing policy though there could be no denying that by merely unlocking further elements within an existing and highly productive design, Nvidia’s campaign for singles glory necessitated an innovative and convincing retort.

As we moved into winter, a new era of gaming was beginning to form. Multi monitor setups were growing in popularity as prices tumbled and refresh rates spiked while the ultra HD resolution of 3840×2160 a fourfold pixel hike over standard HD was soon to be an integral part of any reputable review. Suddenly, over the battlefield, there echoed some ominous murmurings from camp crimson regarding the masterpiece with which they planned to exploit such developments and in so doing, “ridicule” even the mighty Titan. Thus, in October, following almost two years of meticulous preparation, a genuine and inspired successor to the 7970 was born and hoard’s of AMD’s most loyal apologists were treated to a club class flight from Tahiti to Hawaii.

The glittering GPU proudly occupied the centre of the companies freshly built flagship, the R9 290X. Though architecturally derived from its ancestor, it sported a handful of notable discrepancies and innovations. A larger die, 438mm2, though still 30% slimmer than the Titan’s fully fledged “Kepler” and enough to play host to 6.2 billion transistors, 2816 stream processors, 64 render output processors and 176 texture units. A generous 4gb side order of DDR5 was added to the ensemble, some way off the Titan’s 6 but 1gb more than the similarly priced GTX 780 and with the tantalizing inclusion of a super spacious 512bit bus on which to cruise. A highly complex revision of powertune was intended to ensure optimum levels of performance via dynamically regulating temperature, fan speed and voltages far more quickly and in exceptionally fine increments, giving AMD the confidence to set the cards temperature limit to an infernal 95 degrees.

As benchmarks erupted over the internet, it soon became apparent that two years had not gone to waste. Overall, r9 290x appeared to have fulfilled its chiefly aim of overhauling the GTX 780 and whilst it might not have “ridiculed” the Titan, the additional memory on its big red bus proved of enormous assistance at Ultra HD, allowing it to frequently surpass both of Nvidia’s war horses and thus be declared the 4K king. The card also scaled magnificently when paired up in crossfire, and their performance against a tag team of Titans in SLI saw many a green eyebrow raised and singed.!

Many hailed this as the best of all possible outcomes for AMD, whilst others insisted that the card’s shockingly high thermal limit was not high enough to avoid it frequently throttling at its stock settings and that to consistently attain such impressive levels of performance, the user had to “cheat” and set it to “Uber Mode”, which elevated the fan speed from 40% to 55%, resulting in more noise and intolerable heat from a beast that already demanded more wattage than either of its rivals.

Before the fervent debate could even begin to resolve, out of the green gloom strode Nvidia’s next commander in chief. The GTX 780 “ti”, to the casual onlooker, no more than an exact copy of his predecessor, but closer inspection revealed not only markedly higher core and RAM frequencies but a full complement of 15 streaming multiprocessors. In essence, a “Kepler” with ALL the stops pulled out. Double precision units were still lacking but the combination of 16 extra texture units and greater memory bandwidth than even the Titan could provide was sufficient for the card to achieve a narrow points victory over the R9 290x, though when Ultra HD was called for or Crossfired 290s battled SLI’d 780s , many still tossed AMD’s card the bouquet.

The last few chapters in this saga shall be kept brief and simple. Since as the sun began to set over the 28nm era, one could scarcely express the tactics of old Red Beard and Green eyes in any other way. Both had dispatched their top talent to dash the others dreams into cascades of broken pixels, yet the war remained close enough for the most impartial of eye-candy junkies to refrain from proclaiming an outright victor

AMD with a monstrous machination that arguably delivered the ultimate 4K experience, especially in crossfire, but ran hotter and guzzled more from the wall. Nvidia three possible alternatives, one, the Titan overpriced by virtue of unnecessary features for the hard core gamer, sometimes faster, sometimes slower, mostly quieter. Two, the GTX 780, mostly slower but a little cheaper and lastly , the 780 ti, mostly faster, but a little pricier. To this formidable pontoon, Nvidia added a fourth and solution. February 2014 welcomed the GTX Titan Black, a “Kepler” toting general with absolutely no compromise.

All 15 streaming processors bellowing in unison with their double precision cores re-activated, memory back up to 6gb with both its speed and that of the GPU set to equal or greater than for all three predecessors. Though it was difficult to dispute that this definitive interpretation of Nvidia’s masterpiece scythed through more frames than all before it, it’s launch price was the same as the original Titan’s, negating consideration from all but money no object gamers or those that wished to harness the card’s compute power. the reason behind it’s release could be little else than a proud green giant forcefully asserting “because I can”.

The only thing left for him to do, was to turn his attention once more to doubles glory, but Red Beared, having patiently and many would claim, wisely observed while his nemesis played to the gallery, was about to blow his top. If the r9 290x had been a gamble on the customer’s tolerance for heat and noise in the face of a burning desire for benchmark omnipotence, it’s dual GPU counterpart took such  a strategy to logical extremes. What does one get when they add Hawaii to Hawaii? A fine spring morning in April revealed the devastating answer….”Vesuvius”.

The R9 295X went further than any card had hitherto in a bid to bestow us with two bona fide flagship GPUs sitting line astern on the same PCB, with not the merest hint of a megahurt or megabyte sacrificed. Instead, this voracious videosaurus, a pair of legitimate 290Xs, was the first ever to require stock water cooling and its TDP of 500W prompted AMD to suggest a power supply of at least 1000 watts for any yearning to tame it.  What’s that…..GFlops again?  Yes, I know I mentioning less and less numbers, look, not much has changed you see?  Nvidia keeps releasing the same card but with different bits working at different speeds and AMD has just multiplied everything by 2.  If I mentioned the all the stats every time…oh please just look at those damned tables, they took me ages!

On the review front, testing methods were evolving almost as rapidly as the technology under scrutiny, with many sites  now employing sophisticated forms of frame analysis whereby the duration of every frame could be accurately monitored and recorded, leaving no chance of misleading results or for the slightest of skips and stutters to escape criticism. The 295x proved more than equal to the challenge, establishing a new reference level in both raw pace and smoothness for cards housing dual GPUs and like the 290X, excelling at Ultra HD.  A price just north of £1000 might have verged on gross parody to some, it remained proportionate to any alternative which could guarantee such stellar performance…i.e a pair of 780ti’s!

Oh…enough already…

All of which brings us neatly to the last but far from decisive instalment in this wearisome graphical chronology. Having at last exhausted the potential of his captain in singles combat and secured what was perhaps a technical, if hollow victory, old Green Eyes promptly attempted to emulate his sworn enemy in doubling the stakes. What emerged was the Titan-Z, supposedly twin Titan Blacks unified on a breath snatching, triple slotted formation. Well, the truth was somewhat different. The Titan Z might indeed have had all 15 of its streaming processors unlocked on both GPUs and with their full chorus of double precision units, but the maximum core speed of each had, by default,  been governed down to over 100 mhz below that of the Titan Black.

Evidently, Nvidia were confident enough that 12GB of memory (a quarter more than the 295x) combined with a chip that had ultimately proven a tad fleeter than its rival’s in unaccompanied operation, afforded them the luxury of a little discretion, not to mention 125 watts less current. Unfortunately, such prudence was nullified by a price tag of £2300, well over double that of the R9 295X.  Would this really translate into frame rates twice as high or as smooth?  Could such wallet withering requests be justified.  Why not let those experts with no need for cash do the talking and be proud in the face of so many choices in our ability to choose not to choose?