Groundhog Node

You don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone is a saying I used to associate with an ailment that persisted long enough for the sufferer to forget what it was like to feel well and that only once fully expunged, could be identified as something that should never have started.

According to popular culture, perhaps most commonly in the form of song, this phrase has virtually the opposite meaning, referring instead to something useful or rewarding that one takes for granted which, once lost or forcibly removed, causes greater inconvenience or regret than anticipated. Water, food, trees, flowers, music, parents and my 18 piece computer tool-set, purchased for nine ninety nine at a Maplins closure sale, sold for two pounds three years later at a local car boot sale and re-acquired for 5 pounds on an internet auction site.

There is another, far less common saying, which could equally refer to both an ailment and one of life’s overlooked blessings, but because it presupposes that the subject is deprived of whatever is being referenced, this particular slogan could also be said to have far greater commercial viability.

“You don’t know what you’re missing, till you get it.”

At the tech world’s illustrious Computex exhibition in May 2019, AMD’s intuitive CEO Dr. Lisa Su might well have weaponized the expression to seduce the staunchest allies of her employer’s deadliest enemy, Intel, who for more than a decade had dominated their eternal quest for silicon supremacy. In feuds between corporate titans, triumph and disaster frequently depend as much upon the loser’s complacency as the victor’s determination, and almost three years earlier, when a stormy Sky disgorged deeper lakes of prosperity, few could have foreseen the consequences of a Blood Red Horyzen.

Since the Summer of 2006, Intel’s ability to maximise profit and performance whilst maintaining an impenetrable market presence had become, so to speak, regular as clockwork, courtesy of a production model commonly referred to as “the tick-tock cycle”. The initial example of this trend was manifested by the US chip giant’s momentous micro-architectural transition from “Netburst” to “Core”, which evoked a tribe of processors that humbled the fastest on AMD’s roster, thus ending a prolonged and profitable era for the Red Team.

From that point onward, Intel adopted a cyclical road-map whereby each successive wave of products coincided with either an introductory design or a dimensional reduction of the existing process node, otherwise called a “die shrink”, intended to optimise power consumption and economise on manufacturing. The company’s “Core” lineage was extracted from a 65 nano meter matrix, which at the time, compared favourably to AMD’s 90 nano meter “Windsor”, one of over 20 processor families belonging to the latter’s K8 age, which had begun in 2003.

Despite also harbouring two CPU cores and a dynamic energy regulation system branded “cool N quiet”, flagship packages such as the Athlon 64 FX-62 were up to 60% less economical than Intel’s universally vaunted “Core 2 Extreme X6800”. Owing to such dramatic modifications as physically separate dies, double the level 2 cache and the facility to allocate it in accordance with workloads, this iconic “King of Conroes” not only commanded the same bounty as AMD’s rival offering but also also netted a performance boost of at least 20%.

This raging debate used to be restricted to discussion forums hosted by prominent e-tailers and websites specialising in technological news, reviews and analysis. However, as the Internet evolved it propagated to personal blogs, real-time message feeds and the comment sections beneath videos created by annoyingly chirpy vloggers, all desperate to beat their contemporaries to the upload with yet another frantic regurgitation the of the keynote presentation they’d witnessed less than half an hour earlier. These self-righteous rigmaroles were forcefully promoted with such click-bait as “Why you should or shouldn’t buy what I have or haven’t bought.” and their content is best encapsulated by the phrase “Here’s another thing that’s a little faster than this but and little slower than that, which I’m going to take an hour to explain”.

By the end of 2007, under the keen eye of its president and CEO Paul Otellini, Intel’s lithography procedure had been scaled down almost as much as its workforce, though such methodical/scrupulous streamlining was borne out of ruthless resourcefulness, rather than financial necessity. The Core family’s 45 nano-meter successors, collectively christened “Penryn”, permitted up to four separate cores to contentedly co-exist beneath the same heat-spreader.

Coupled with DDR3 memory, a further third of cache and updated chip-sets for both the mainstream and elite markets, the wily dual-died Wolfdale and its quad handed half-brother, the Yorkfield, outperformed their respective seniors by small but credible margin. AMD meanwhile, remained a whole node adrift and worse, had failed to evoke a scintilla of extra speed from their 65 nanometer transition. Hence neither the dual cored “Brisbanes”, nor their quad dextrous descendants, the “Agenas”, themselves the first “Phenom” branded processors to emerge from AMD’s k10 era, could carve any impression upon convoys of ageing Conroes and Kentsfields, allowing Intel’s proud and youthful Penryn to compound their master’s healthy lead.

Another clamorous “Tock” around the clock invoked what even AMD’s most ardent activists might well have conceded was Intel’s finest creation to date and with hindsight, for several aeons thereafter. Node “Nehlem” duplicated its forerunner’s underlying dimensions, but re-equipped its speediest quad-core derivatives with hyper-threading, a notion best analogized by likening each physical processor core to a human arm, and each core’s “virtual thread” to an extra hand.

The Nehlam affected major changes to several native elements within Intel’s long-established chip-set framework. The hitherto traditional “front side bus” was decommissioned and with it, the potential for deteriorating stability as core counts rose and the over-clocker’s frustrations parallelled those of a fighter pilot in a hot air balloon. In its place, the compulsive tweaker, was rewarded with a broad selection of BIOS based variables for controlling a series of multipliers, ratios and frequencies pertaining to the CPU and system memory.

The most influential was the base “B” clock, an adjustable divisor that ultimately dictated the velocity of the host computer’s vital components and served as incremental “building blocks” for determining the sweet spot. These bold and practical solutions were accompanied by the re-introduction of SLI to Intel’s top and mid-level chip-sets, the consequence of a lateral licensing move by Nvidia to compensate for the Green Eyed Goliath’s grudging and highly pertinent exit from the motherboard market.

Across the battlefield in Camp Crimson, seasons of profound discontent dragged on and by the winter of 2008, even fire from a figurative “Dragon” did little to warm the hearts of dejected red-blooded fans. Though AMD’s ripest silicon and its concurrent platform revisions had brought it level with Intel in terms of core population, lithography and memory strain, the performance, efficiency and value exhibited by the resulting “Phenom 2 X4” processors, was somewhat less than phenomenal. AMD were not currently catering for the market’s biggest spenders, but their efforts to seduce an ever-thriving demographic of thrifty shoppers who ranked loose change above customer loyalty, were contested with decisive success. This pattern persisted throughout three tiresome annuls of Intel dominated death matches with the ferocious Lord of fabricators possessing a Coup de gras to parry each of its foe’s flailing sucker punches.

The X4 955 “Black” Edition, released in April 2009 and the fastest triplet from the “Deneb” stable. Itself a solid package bearing an attractive price, but overmatched by Intel’s lowliest “Bloomfield”, the i7-920, thanks to the latter’s hyper-threaded cores and superior IPC rating, which also allowed it to pull ahead exponentially when overclocked.

The X4 970 materialised over a year later, demonstrating that there was still oscillations to reap from Deneb’s DNA. At under $200, it also appealed to the frugal, but for the same investment many had already bagged an I5-760, perhaps the most ubiquitous member of the company’s cannily promoted “Lynnfield” range. This particular incarnation was stripped of hyper threading, but still edged out the opposition in all but a handful of applications and developed the same progressive advantage if overclocked.

If a quartet of cores couldn’t eradicate AMD’s arrears, perhaps a sextet would. Christmas 2010 welcomed the last in several deployments of six tentacled “Phenoms” founded upon AMD’s “Thuban” fabrication template. Their paramount embodiment, the 1100T, was only a little dearer than its ancestral cousins and managed to exchange convincing blows with everyone of Intel’s cost-conscious alternatives, including the aforementioned i7-920, even nosing ahead ahead when assigned with arduous multi-threaded tasks. But Intel had been busy too, and with more than reciprocal enhancements. Aside from acquiring three separate companies, the titan of transistors had already made the lithographic transition to 32 manometers within its luxury and economy product lines and now, it was about to bring/set mainstream radicalism crashing down/loose upon its ruby nemesis. As 2011 dawned, the spectacular “Sandybridge”, a feat of Intel’s resourceful Israeli workforce, converted diminishing returns into quantum leap.

Still only four”arms” strong, but with eight “hands”, the launch party’s star attraction, the i7 – 2600k set its buyer back over 300 dollars, 20% more expensive than its task juggling opponent and yet, in its untapped state, Intel’s revolutionary architecture generated a relative performance increase of 40%. This discrepancy was replicated in other comparisons between chips from the same two lineages, leading experts, pundits and deserters of AMD’s dwindling militia to unanimously declare that in this instance, the speed justified the surcharge. The Sandy Strike-force unleashed a veritable “desert storm”, blitzing every benchmark beneath the scorching sun with remarkable efficiency, garnering equal adulation from the creative and the recreational. Videographers saw their workflows streamlined by “Quick-Sync”, a unique encoding method executed by the Processor’s graphically attuned deputy, whilst gamers experienced frame rates that surpassed those achieved by Intel’s own hexa-cored colossus, the “Gulftown” 980x, an “extreme” badged SKU of the giant firm’s “Westmere”, which sold for triple the cash and consumed up to 30% more energy.

After the roaring winds and billowing clouds had subsided, the only “Phenomenon” in site was the silvery moon, as it cast en eerie glow across acres of silent emptiness and from afar, the anguished laments of Deep Red’s most dearly devoted rang hollow around towering dunes. Spring and Summer concluded with no hint of a threat to Intel’s reign of teraflops. Then, as crisp Autumn leaves caressed the surgery sand, a distant and distinctive rumble fell upon expectant ears. Too regular for rolling thunder and too low for a swarm of locusts. As the sound drew nearer, advocates on both sides of the silicone divide sensed that transistors were being primed for the next confrontation were being sewn, and AMD had deployed the heaviest possible artillery to carry out the opening attack.

With a maximum of 8 tangible cores and power envelopes resembling those of its parentage, The Bulldozer was arguably both a blessing and a curse, on the positive side, it allowed AMD to once again compete nano on nano with Intel though on the negative, its chiselled die had failed to realise a commensurate improvement in conservation. But famished supporters of the scarlet order had no scruples regarding conservation. Instead, many argued that the product’s conservative price would rationalise its long-term running cost, at least, until they’d had the opportunity to verify whether their new toy’s cosmic stock frequency could be boosted enough to subdue their sneering opposition and punish turncoats for their premature treachery. Regrettably, the Bulldozer fell short of sundering shifting sands.

The impressive core quota was not quite what it appeared, and a detailed inspection revealed that AMD had re-defined its cores as “integer clusters”, which were allotted in pairs to physically separate modules. This meant that, depending on the CPU, eight, six and four “integer clusters” were confined respectively to four, three or two modules, with each cohabiting couple being forced to share a single floating point unit.

Though closer to material replication than Intel’s hyper-threading, it was a far cry from what would have been possible had each core been truly self-contained , and equipped with a exclusive set of sub-components.

The generous frequencies also proved to be a false dawn, since they were not complemented by a rise in instructions per cycle.

Returning to our biological metaphor, if we picture each processor core as an arm with one hand, we can also visualise each instruction as an orange and the cycle as the act of juggling. The processor’s megahertz metric could then equate to the number of times each hand can juggle through every one of its oranges in a single second. For the sake of this analogy we will discount both hyper threading and AMD’s effective implementation of it since it is not possible for every “physical core” (arm with one hand) or “virtual thread” (extra hand) to function in full unison, figuratively they could only split the oranges between them.

Thus, The Bulldozer’s brawniest hopeful, the “Zambezi” FX-8150, was able to accommodate twelve oranges (instructions) in each its 4 hands (cores) and, at its default speed of 3.6 billion cycles per second (3.6 gigahertz), could potentially juggle up to 173 billion oranges every second, a most juicy prospect for its eager adopters. However, Intel’s now mature and revered i7-2600k could casually fling no fewer than sixteen oranges with any one of its four sandy tendrils, making a stupefying theoretical total 218 billion per second. A markedly sweeter breakfast and a bitter blow for the raging Red Bull.

As reviews propagated the tech ether, the results did not defy the polls. Once again, AMD were slower, hotter, greedier and still couldn’t convincingly offset these deficits with their aggressive pricing strategy. Out of the box, Intel’s 40% lead was barely dented, and though assiduous tweaking allowed the Fiery FX to snatch a record breaking overclock of 5ghz, the expertise, thermal management and electricity necessary to even approach such a threshold, rendered the merits of doing so all but redundant. When assessed against its adversary, even with lacklustre cooling and limited technical knowledge, these compulsory investments transformed an attractive bargain into cumbersome extravagance.

AMD were further humbled by the simultaneous appearance of an even sharper “Sandbagger”, the i7-2700k, and when their own range-topping response, the FX-8170, was cancelled due to excessive power consumption and relative mediocrity under all but the most sustained and intensive scenarios, any doubt over Intel’s dominance was lain decidedly to rest.

Having appeared so formidable on its resolute journey to the front line, The Bulldozer’s tracks promptly stuttered and stalled beneath the Sun’s anvil and the colossal contraption slowly sank into a gaping maw of quicksand, seemingly doomed to share a natural and nameless grave with the fallen Phenom.

With a fourth consecutive victory, and perhaps the most effortless to date, one might have assumed that Intel’s savants of semiconducting would pause to admire their magnificent laurels. But the devious die-conjuring overlord knew neither respite nor mercy and aspired nothing other than to solidify his brutal tyranny.

AMD’s conspicuous absence from the wealthy enthusiast‘s desktop had been influenced primarily by the company’s sensational acquisition of ATI and an inherent obligation to perpetuate the latter’s “visionary” vendetta against Nvidia. This monumental challenge had necessitated a militant re-structuring/routing of resources, leaving their top-tier customers indefinitely forsaken and disposed to seek gratification elsewhere. Now, after a prosperous four year lock-out, Intel were again eager to indulge their broadening niche of opulent loyalists.

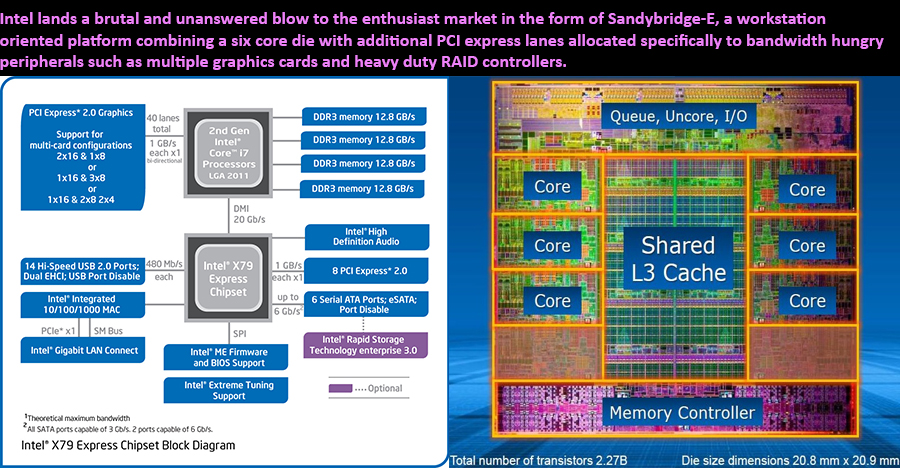

November 2011 witnessed the Sandybridge-E, a trio of monolithic CPUs bred for bleeding-edge workstations and pitched at the creatively inclined gamer. Their foremost protagonist , the i7-3690x boasted six hyper-threaded cores with a turbo range reaching 3.6 gigahertz and almost twice the tertiary cache of its lowlier siblings.

The following spring, with AMD still silent under a bleak and baron wasteland, the emergence of Ivy Bridge allowed Intel to further tighten its stranglehold over a growing fraternity of cost-cutting defectors, and move another rung down the lithographic ladder.

By now, multiple voices of reason were declaring that AMD’s reputation was terminally tarnished the chances to restore faith within their tapering ranks ebbed away like floodwater as Summer drifted by. Even tougher would be the task of recapturing hoards of deserters, all of whom were gleefully relishing over-clocks, frame rates and benchmark scores that may soon immortalise their new found proclivities. Then, precisely twelve months after the Bulldozer’s soul-destroying fate, the desert sand turned a rusty shade and from below, a resonant booming rent the air. The giant dunes began to shudder, sending golden halos spiralling into a vast blue expanse and all at once, a mighty Piledriver, burrowed from its forefather’s place of rest.

Fundamentally, The Bulldozer’s souped-up remix was a chip off the old wafer, and critics wasted little time in noting AMD’s failure to mirror Intel’s proportional reductions. Indeed the Piledriver had not shrunk one single nano-meter, but a year of hushed rumination had elicited more than empty pledges and fancy flow charts. Where the Bulldozer had puffed and spluttered, the Piledriver purred and punched.

The improvements were subtle but voluminous. More accurate branch prediction to enable sharper responsiveness in routine tasks. Optimised secondary cache handling to attenuate the latency introduced by the hardware’s shared constituents. Most crucially, though the CPU’s voracious voltage demands were identical, AMD’s Die Hardests had utilized them to extract a significant speed bonus.

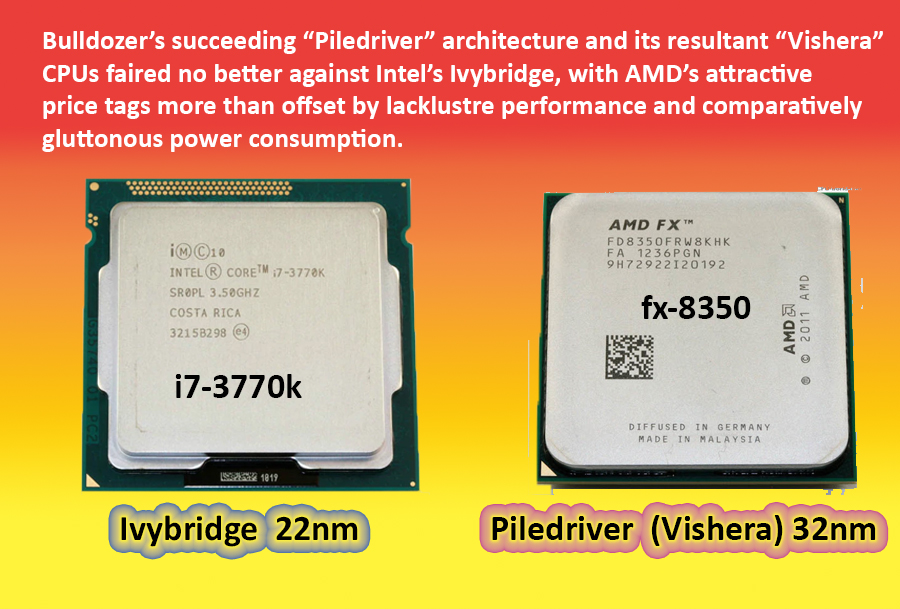

But would such refinements be apt to wrestle Ivy Bridge from its tenacious roots. Could they prevent Intel’s reigning champion from clinging to the ultimate accolade, and liberate millions of indoctrinated patrons from its tangled clutches. The Piledriver’s thunderous hammer initially brought forth a quartet of processors, all bearing the moniker “Vishera”. Their mightiest was the FX-8350, which could be obtained for under 200 dollars, a 40% saving on the Ivy Bridge’s principal protege, the i7-3770k. But Intel’s chip also harboured some commendable optimisations.

Its 22 manometer die could now ramp up to full steam for a remarkably meager 77 watts, practically half of what the FX required to fire on all cylinders. It also debuted a brand new breed of transistor, the TriGate, which Intel claimed economized on living space and drastically enhanced performance at conservative voltages. As to the benchmark battle, one could have easily theorized that jaded journalists had dredged up a bunch of bar charts from the previous Autumn, tinkered with their colour schemes and altered the data labels to denote the incoming products.

The gap was as constant as political propaganda. AMD’s had made progress but Intel’s defense was water-tight. The Visheras’ prodigious speeds translated to marked gains over their Zambezi counterparts, but these were mitigated by the Ivy Bridge’s ability to execute more instructions at any given frequency. Only in the value stakes could the Piledriver’s legacy claim to have clawed back a measure of AMD’s distinction.

Ivybridge’s grasp over the competition was absolute, but a strain of objective hobbyists had complained that Intel had cut-corners in the factory to raise margins out of the warehouse. One such compromise in quality was to apply a sub-optimal thermal interface between the processor’s die and its heat-spreader, a decision that might well have passed undetected had it not been for progressively forensic diagnosticians, whose interests in preserving warranties were nullified by a burning ambition to expose the willful oversights of a major corporation.

Nonetheless, Intel’s streak now stood at five emphatic wins. Their factories were churning out chips at the rate of a fast food franchise and with the grace of a world class symphony orchestra. As another Christmas elapsed with every customer’s silicon fantasies fulfilled, their chosen cyber-saint grew larger, richer and ever more ruthless. By the middle of 2013, no fewer than nine companies from across five countries had been consumed by Santa Clara’s Corporate Carnivore, extending its business portfolio to the software and services industries. Its cavernous foundries hummed in ominous unison as legions of lasers stood poised to slice fresh wafer.

Intel’s effective monopoly had allowed its Nehalem platform to set a profitable precedent, namely that the company’s premium and mass produced solutions were no longer interchangeable. Each range of components incorporated its own chip-set, socket pin layout, bandwidth allotment and memory configuration, meaning that buyers who’d prioritised on price when selecting a processor and motherboard, incurred a reduced choice of upgrades as their needs broadened, unless they were prepared to replace their entire system.

With such a forlorn lack of competition, what little protest arose carried pathetic momentum, and as if to to emphasise their strategic division of clientele, Intel also flipped the launch schedules of both product lines, allowing the money-savvy to savour certain noteworthy aspects of its latest technology before the elite.

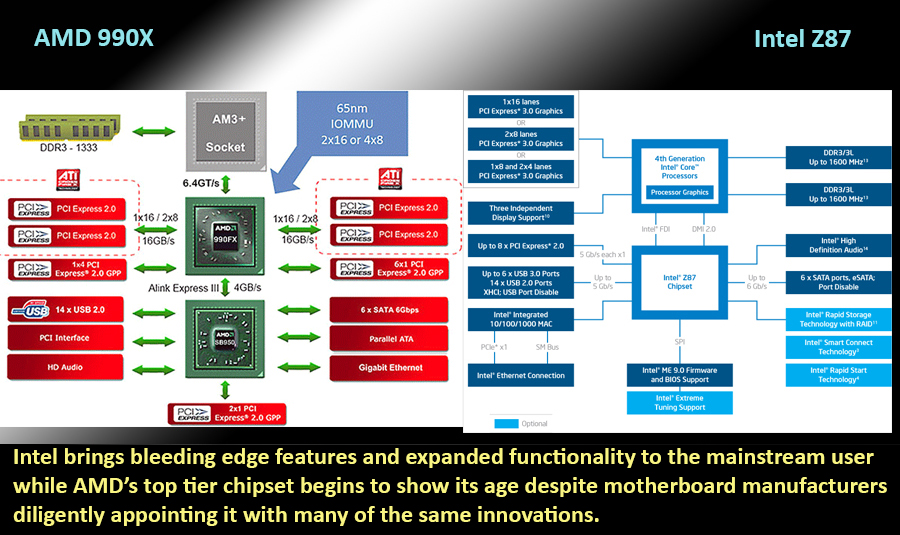

In June 2013, generation Haswell followed suit, and though its accompanying z-87 chip-set offered little in the way of innovation, Intel’s proactive shift in commercial focus led to an almost stupefying selection of motherboards from renowned manufactures, all smothered with enticingly rich feature-sets and lavish third party integrations like the PEX 8747 from PLX, occasionally known as The Magic Multiplexer. This true marvel of engineering effectively doubled or quadrupled the data transfer capacity between the host PC’s CPU and its PCI slots, allowing a larger number of consumptive peripherals to operate at their functional extremities.

Its practical intention was to enable less profligate part pickers to assemble builds consisting of multiple GPUs, or which merged a loan graphics card with a high-speed network adapter, or card mounted solid state storage, without being encumbered by chip-set’s inherent limitations.

AMD remained financially constrained to one foundation, but the now mature 990X had also generated an array of exceptional interpretations, each decorated with a similar abundance of accoutrements. Contrary to Intel, AMD’s chip-sets supplied PCI bandwidth to devices exclusively, instead of distributing the lion’s share from the system’s processor and numerically, the 990x provided almost twice the number of PCI lanes of the z87, though a substantial portion of these lagged one revision behind the latter and realized only half the transmission rate.

Haswell’s introduction triggered a relatively muted reception, perhaps because after Core, Nehalem and Sandybridge, statistical analysts had come to associate nascent architecture with the higher gains than honed designs.

Debut features such as ultra carbon-efficient operating modes, more intuitive execution algorithms, a leaner platform controller hub and a voltage regulator situated inside the processor alongside fortified Graphics facilities, all sounded impressive at the keynote preaching and looked pretty on PowerPoint slides. But once the hype and hearsay had subsided and cold hard reality held Haswell’s transistors to the proverbial flames, the net improvement bestowed by these and other innovations was decidedly underwhelming.

The i7-4770k spearheaded a brigade of launch products and was the i7-3770k’s spiritual successor. Once married to the the Z-87, it presented a choice of base clock and RAM ratios to attain the fastest possible setup, though even when armed with such BIOS trickery as was previously an enthusiast’s sole privilege, Hawell’s heftiest hitter accumulated an average gain of less than 10%, virtually identical to the Ivy Queen’s lead over her Sandy originator.

Its core tally was stuck at four, its nominal and turbo frequencies were unaltered, its power envelope rose by 7 watts and its increased IPC rating was not wholly reflected under synthetic or organic conditions. From an over-clocker’s perspective, the Haswell again yielded diminishing returns. Were Intel commercially freewheeling as a consequence of AMD’s repeated misfires? Was the persistent absence of healthy competition arousing complacency within a business whose revenue was the envy of an intergalactic emperor, and presently totalled ten times that of Big Red’s? Before anybody could ponder further, AMD broke its semi-conductive silence with a cataclysmic blot out of the blue.

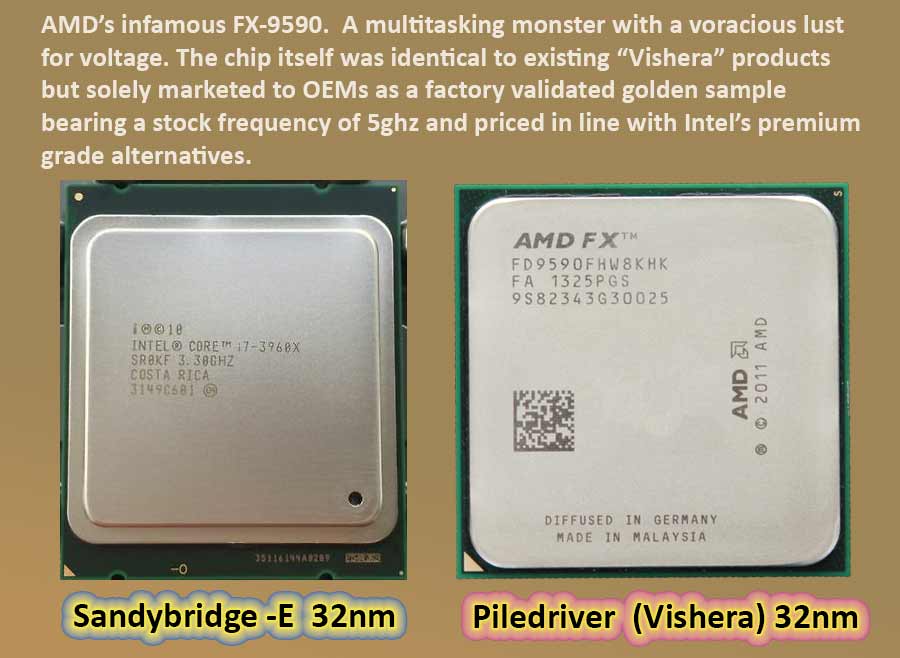

If CPUs were wrestling moves, the Fx-9590 was the proverbial Tombstone Piledriver and as close as AMD had come to a fully-fledged Flag-chip since the Windsor’s wiliest Wizard had waged war against Colonel Conroe some seven Summers earlier. Bursting onto the shelves barely a month after the Haswell had paraded its charms, these most vicious of “Vicheras” were hand picked and individually verified to reach the holy grail of 5ghz right out of their spartan OEM packaging, 700mhz swifter than the 8350, and the very speed that had secured a world record for its generational godfather, The Zambezi. Best of all, it required no new socket to sing.

Speculation saturated cyberspace as unsettled murmurings would pervade a cinema just before the third instalment of a blockbuster franchise which hard-core aficionados said would be awful, paid to see anyway, then went on Youtube to condemn it in a 90 minute rant about capitalist picture studios indelibly tarnishing a sacred legacy. Could this reckless uppercut be an exquisitely timed equaliser? Would it at least suppress the galling mockery from Intel fans, whose comparatively ancient relics were still potent enough to ensure that they ranked further up Cinebench’s league of legends, or stayed crucial frames ahead in a tie-breaking/tournament winning Deathmatch.

As NDAs were lifted, an avalanche of graphs, stats and turgid analysis flooded the internet, as several million index fingers began to scroll. The gap appeared to have narrowed and AMD’s copious injection of pace had allowed the Piledriver’s ultimate rendition to mount a convincing challenge within the realm of professional creativity. In video encoding, photo editing and 3d composition, General Vischera had overwhelmed Sandy and Ivybridge’s finest main-streamers and was snapping at Heir Haswell’s heels. But once graft turned to gaming, its octet of infernal engines faltered and a solemn sigh emanated from AMD’s crestfallen acolytes. From there, matters worsened. The liberties that AMD had taken to prepare their prized pretender for its pivotal confrontation were both drastic and costly. For one, its TDP had ballooned to a staggering 220 watts, by far the highest of any consumer class CPU and a requirement that many supposedly compatible motherboards were ill-equipped to support. Only those with herculean voltage regulators, bulletproof capacitors and the most sophisticated power phase circuitry were officially approved to satisfy its rabid appetite. Then, there was the exorbitant price tag of $920, which placed the product beyond the budget of its logical demographic and directly in the firing line of Intel’s imperious Sandybridge-E, a showdown which it lost by unanimous decision.

AMD’s attempt to waltz back into a market it had snubbed for so long had apparently incurred Intel’s wrath, for two months after the Piledriver had hammered home its masterpiece, the Ivy crested its turret. Intel’s best-heeled clients were presently trailing the company’s mid-tier user-base by two whole eras, having sat patiently and observed the charms of Ivybridge and Haswell empower the PCs of their penny pinching colleagues. By Autumn 2013, 22 months after Sandybridge’s swan-song had made a minor dent in their finances, idol fingers were beginning to twitch. Ivybridge’s Alpha trilogy encompassed all of the upgrades that had bolstered their beta siblings, and melded them with the endemic fortes of their extreme elders.

Supplementary cores, spacious cache and greater auxiliary bandwidth. To committed investors in Intel’s elaborate Patsburg chip-set, they were a seductively simple drop in replacement. But some who’d instinctively added the thousand dollar monarch (i7-4960x) to their virtual shopping carts and were about to auction its predecessor to a cagey Ebay dealer, hesitated when a hasty Google search revealed its minuscule advantage, hardly a hair’s breadth over 5% on average and with decidedly inferior scope for overclocking. Meanwhile, a contingent of disgruntled videographers fulminated over the continued absence of Quicksync, the magic on-die transcoder that allowed extrovert broadcasters to live stream their unboxings, frag fests and rage-quits, before editing and converting the recorded footage to a phone friendly format in a fraction of the time.

Intel’s exploitative class segregation was causing civil unrest. The aristocrats were convinced that the workers were becoming overly privileged as their own exclusivities dwindled, and the workers were feeling increasingly short changed by their unseen yet omnipresent ruler.

Though no amount of objection would force Intel into attentive diplomacy. The only way to rattle Chipzilla’s cast iron cage, so said his critics, was to direct your business elsewhere. But Intel had every niche stitched up tighter than an Egyptian sarcophagus. Battalions of their Xeons energized server farms across the globe, forming the backbones of multi-billion dollar e-tailers, cloud storage and service providers, web hosting infrastructures and data harvesting networks. Its mobile products powered the portable solutions of leading International vendors. They had formed the brain of Apple’s Macbooks since 2006. Microsoft had recruited them for their heavily publicized hybrid “Surface” tablets and their desktop packages populated ranges of prefab systems from such mass producers as HP, Dell and Lenovo and were eagerly sought by acclaimed boutique brands for use in glamorous custom builds. Enterprising DIYers were in the same predicament, all paths lead to back to the lair of the Blue Beast.

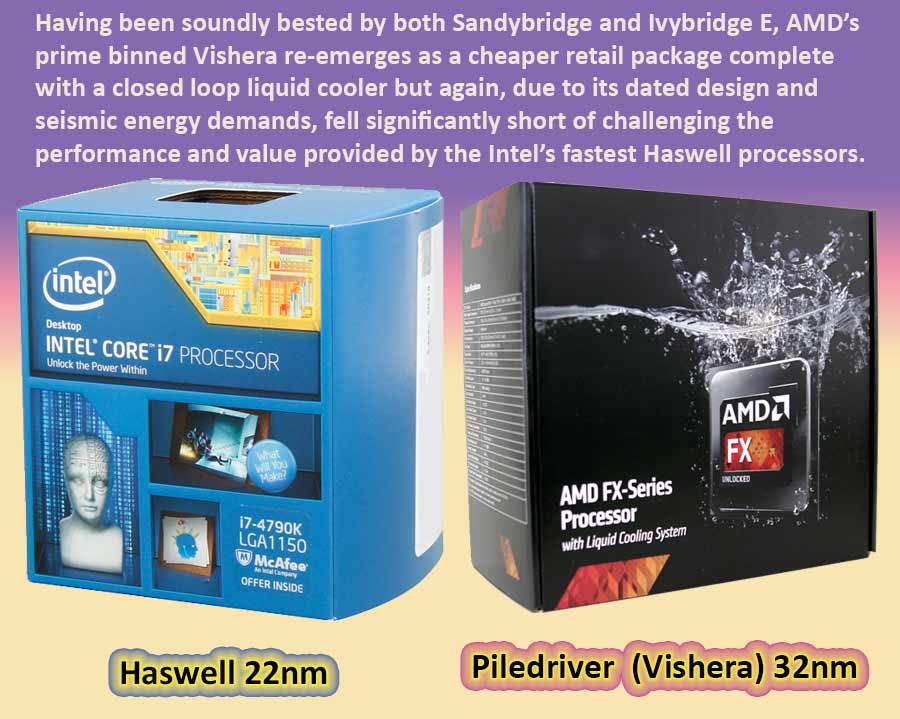

And In November 2013, when AMD declared it had no plans to renew its premium chipset the following year, or arm its AM3+ socket with deluxe variants of what was envisaged to be the the Piledriver’s heir, Steamroller, the PC industry teetered on the precipice of a full blown Intel autocracy. Throughout 2014, Intel flexed its fabs and inflated its prices. Summer unleashed a demonic duo of supercharged Haswells aptly codenamed “Devil’s Canyon”. These top of the line i5 and i7 refreshes, displaced their equivalences from the previous equinox and utilized a minuscule four watt TDP increase to add 100 and 500mhz to their respective base and boost frequencies. With the aid of exotic aftermarket cooling, tinkerers took nanoseconds to drive both chips towards the notorious 5ghz threshold and, thanks to the exponential gains granted by its elevated IPC rating, leverage more than 10% of additional performance. AMD, being out of ammunition, hastily relaunched their supreme Vishera in retail attire, slashed over half off its original bounty and join forces with Cooler Master to provide a bundled closed loop heat-sink. It didn’t matter, for even if the Piledriver’s definitive offshoot had the not devoured more than double the wattage of Haswell’s hottest property, Intel’s package now romped every benchmark, game and application without complex intervention, and remained better value even if purchased with one of Noctua’s class-leading thermal dissipators.

Haswell’s second coming also germinated a refreshed chip-set, the z-97, which aside from offering intrinsic compliance with the Demonic Duo, also facilitated a revolutionary form of data storage which replaced traditional hard disks and solid state drives with ultra low-profile modules that resembled generic system memory, and were affectionately known as “Gum sticks”. Though they conserved valuable space within crowded or compact computers, their prevalent purpose was to eliminate the bottleneck imposed by the arcane SATA interface and employ additional PCI-E lanes to accelerate data transfers.

Just as the enraged aristocracy were preparing to abandon their antiquated uber-rigs in favor of what they believed would be a more enriching populist lifestyle. Intel’s inspired artisans answered their distress calls by serving up Haswell-E in tandem with fresh flagship instigator, the “Wellsburg” x99 , bringing its precursor’s three year lifespan to a long awaited conclusion and seducing starved elitists with the chance/opportunity for a first bite at DDR4/to be the first to sample the delights of DDR4. True to form, Haswell-E’s head honchos numbered three, with each bearing a moniker, price and specification in keeping with their retirees. And the resultant rafts of maternity retained all of the luxuries to which enthusiasts had grown acclimatized, with the usual suspects Asus, Asrock MSI and others, adorning their masterpieces with sumptuous arrays of of spoils, including denser and swifter connectivity, BIOSES bursting with sophisticated tuning and monitoring options, some controlled by proprietary accessories, superior on-board audio and of course, ample accommodation for miniature form factor storage.

Though AMD’s canny ingenuity soon ensured that such emergent technology was also supported by their valiant vintage 990fx, there was no pilot fleet enough to light up the diodes of a Fatal1ty fighter Jet and do battle with the Brutal Blue Baron. But just before Intel set their aims “Sky-High”, Hawell needed to “End Well”, and little did any insider know that the impending die shrink would be the most politically influential for a decade, and for all the wrong reasons.

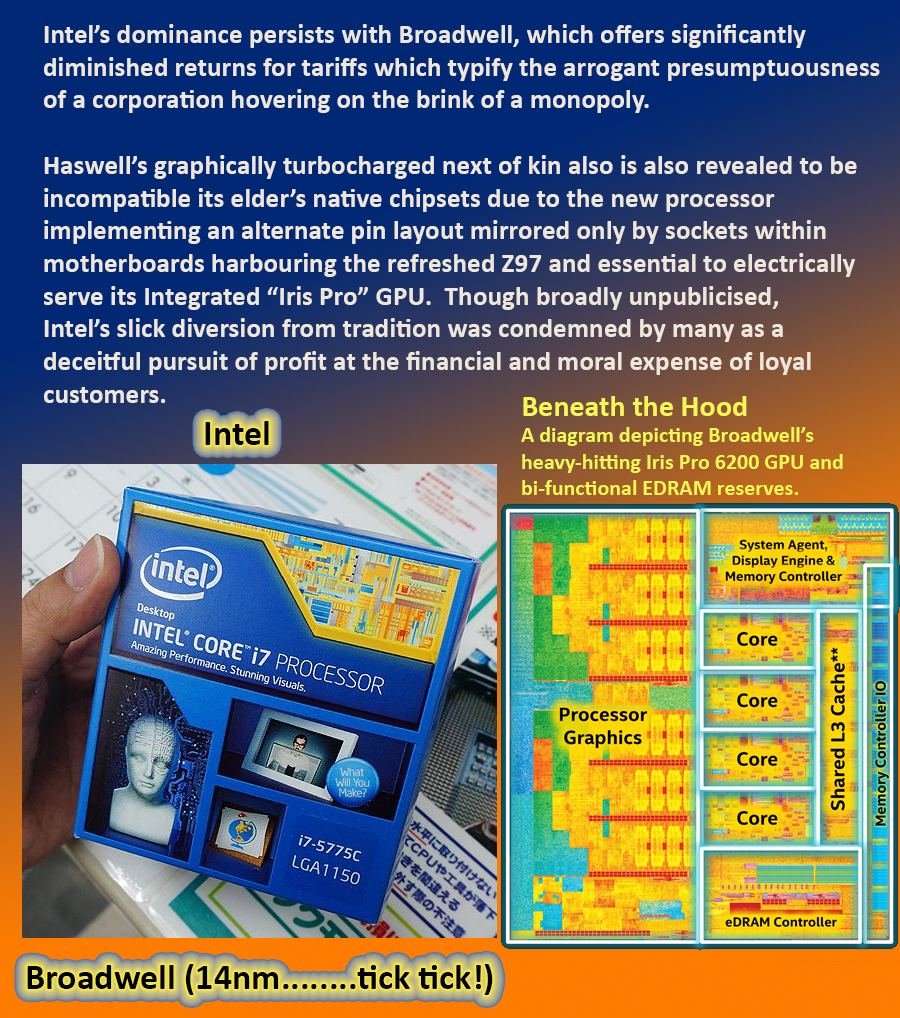

The 14 nanometer Broadwell roused scarcely a whisper across cyberspace, broadly because its central-tier consisted of only two SKUs ostensibly intended to demote the Devilish Hawells, yet neither out-classed its genetic senior in any useful regard save for burning fewer watts to fulfill its duties. Indeed, when subjected to rigorous multi-threaded workloads, both Broadwell’s i5 and i7 variants trailed their Haswellian doppelgangers by virtue of of a cut to the former’s core frequencies. Its sole saving grace was “Crystalwell”, a beefier on-board “Iris Pro” GPU fused to a generous reserve of embedded RAM that significantly improved gaming performance and dually functioned as level 4 cache in the presence of discrete graphics card.

The Broadwell also excelled at content manipulation, where this expanded memory could also be harnessed by the arcane magic of Quicksync to further reduce trans-coding times. But when weighing these pros against a steeper price and the lowest headroom for overclocking in four generations, the majority of Intel’s veteran converts elected not to tamper with their infallible workhorses, each one configured, constructed and tuned to perfection, and all comfortably dependent on the fruits of harvests gone by. The tiny faction who succumbed to profligacy, were in for an unwelcome surprise. Since the twilight of the Netburst era, it been customary for Intel’s desktop platforms to support every processor realized from one full tick-tock cycle.

An ancient motherboard such as the Corporate Kraken’s original “Bad Axe”, based on its venerable “Glenwood” chip-set could grant life to either 90 or 65 nanometer Pentium D CPUs from the “Smithfield” or “Presler” families. Asus’s P7T Supercomputer, with the redoubtable Tylersburg X58 at its heart, afforded all “Bloomfield” and “Gulftown” i7s universal compatibility whilst Sandy Bridge’s mainstream mobilizer, “Cougar Point”, as exemplified by Asrock’s plucky P67 Pro 3, gave every circumspect technophile the chance to grasp Ivy when they felt so inclined. Naturally, those who’d invested in Haswell’s maiden enabler, “Lynx Point”, had assumed that Intel would adhere to tradition and afford them the potential to “Broaden” their horizon. But reports promptly confirmed that, despite the dimensions and contacts points of both processors being physically indistinguishable, the pin configuration on refreshed z-97 boards harboured electrical discrepancies that were essential to initialize Broadwell’s visionary virtues. Thus, to a high-end Haswell owner already in possession of a respectable graphics card, the cost of procuring a product whose sole selling point was a GPU that would only benefit video encoding and moreover, perform worse in all other notable respects, amounted to over $500.

The prevailing media nonchalantly disregarded Intel’s controversial departure from form, choosing instead to marvel at Broadwell’s transcendent “Iris Pro” and interpreting the chip’s ill-timed genesis as evidence of its creator’s desire to revolutionize the concept of integrated graphics. Reviewers not on Intel’s shortlist to be blessed with golden samples, viewed it as another example of flagrant avarice. Intel shrugged off such criticism as briskly as they reaped profit. Their quarterly earnings were steadier than tungsten carbide and their net income was set to top $10 billion by the end of 2015. Their acquisition portfolio now stood at sixteen and had spread to the domain of wearable technology, including devices conceived to implement virtual and augmented reality. Meanwhile, AMD’s CEO, Rory Read, had stepped down following three tempestuous years manning the helm and Tech Vlogs and podcasts were replete with agitated pleas for the incumbent commander in chief, Dr. Lisa Su to step up and salvage a sliver of dignity. But their cries echoed mournfully around The Scarlet Army’s windswept barracks, whose depleted infantry appeared roundly engaged in resisting Nvidia’s polygonal prowess. The immense pressure perpetuated by two aspiring digital dictatorships, each delivering increasingly destructive payloads and converging on their common foe in an ominous pincer movement was beginning to shake AMD to its ruby cores.

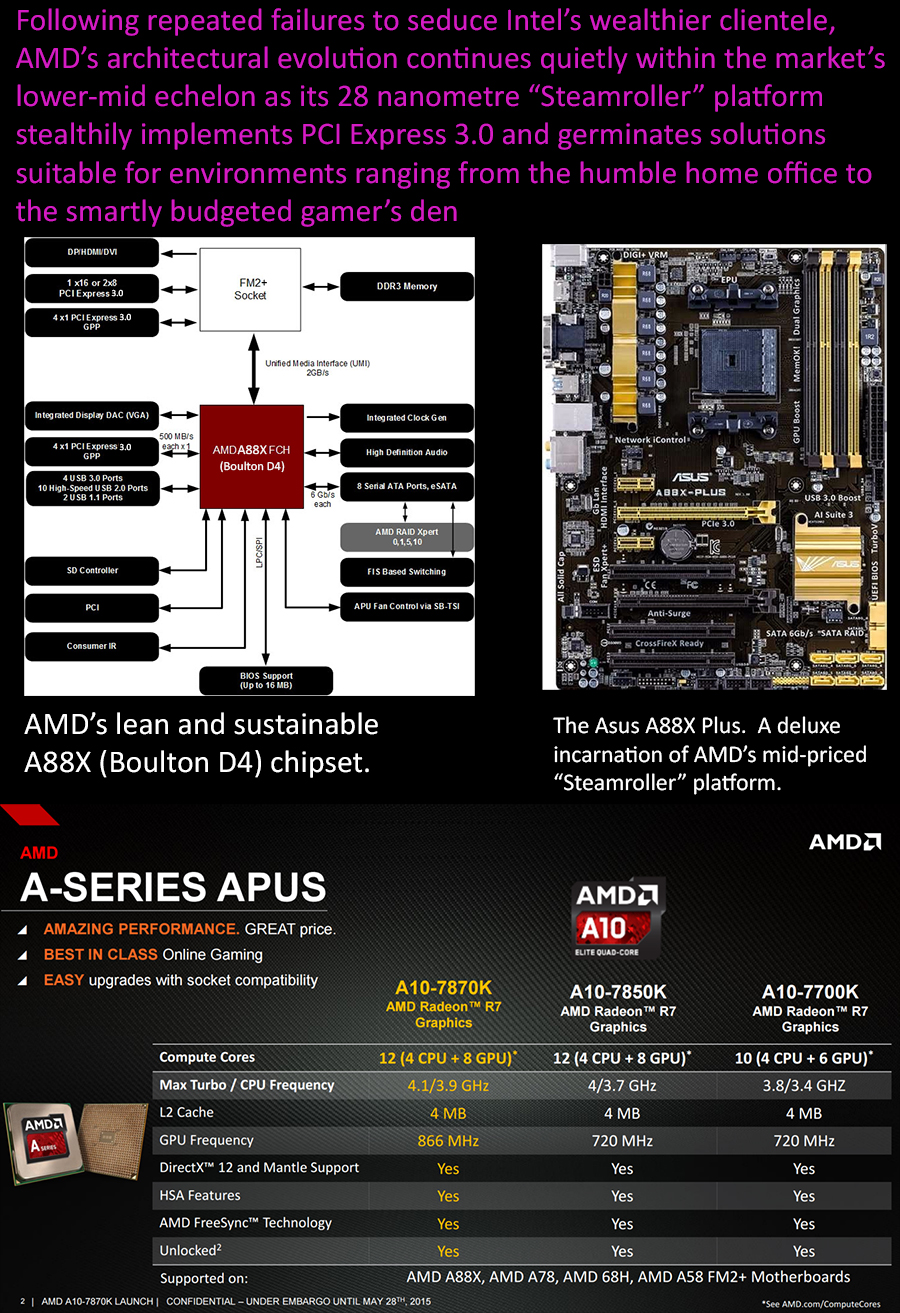

While the Piledriver spiraled into a sorry decline, its descendant, Steamroller, was only ever fated to assuage modest needs. Biologically, it was Bulldozer’s tertiary incarnation and had subtly emerged more than a year earlier during its ancestor’s titanic struggle throughout the market’s upper-echelons. The platform comprised a new socket and a tetralogy of chip-sets, the most capable of which, at long last, furnished AMD devotees with the third revision of PCI Express. But the A88X, or Boulton-D4, was in truth, the peak of a budget-oriented product pyramid and its precursor, the Hudson-D4, had in turn represented Piledriver’s lower-mainstream alongside a corresponding trio of subordinates. The Hudson had offered appreciable versatility to the under-privileged user who favoured “bang for the buck” over “bang for the bank”. The student cautious of their burdensome loan who casually coded by day, browsed, played and socialised by night and craved a decent set of variables with which to gratify their tweaker’s instincts. In enlisting Boulton to pilot PCI’s latest standard, AMD were evidently attempting to remould a cut-price compromise as a premium package in the absence of a genuine heir to the 990FX.

The platform’s compatible processors were APUs, or “accelerated processing units” and housed a pictorial assistant in the same fashion as Intel’s bargain and mid-priced solutions had since the inception of Westemere. Christened Kavari and Godaveri, and sporting transistor gates measuring a svelte 28 nanometers, they were also their host system’s prevailing source of peripheral bandwidth, yet even when supplemented with that delivered by the chip-set, the transmission limit and data lane count were unbecoming of a true desktop thoroughbred.

Nonetheless, Colonel Kavari, the A10-7850k and Commander Godaveri – the A10-7870k, inevitably benefited from their creator’s formidable credentials as a GPU pioneer and were able to trade ornate textures with the integral talents of Haswell and Broadwell at conservative resolutions, though the very instant that optical duties were diverted to a dedicated video card, or lighthearted recreation gave way to productive heavy lifting, the feisty little APUs were left floundering in the Blue Chippers’ turbulent wakes and moreover, eclipsed by Big Daddy Piledriver.

As AMD’s most mindless optimists tried to render a rosy picture, those more centrally aligned were past persuasion. They’d waited with the patience of a saint who was waiting for another saint to grant sainthood to an irredeemable sinner. They’d suppressed the recurring urge to sell their ruddy souls with nostalgic reminiscence. Winter mornings spent staring longingly through the window of a bedroom littered with tools, cables and a hundred stray screws. Waiting with a pounding heart for the first glimpse of a courier’s van. Signing an illegible scrawl before accepting their parcel with trembling hands and a jovial/convivial nod to the driver, knowing that the freshly forged FX-60 within would propel them into a pixelated paradise beyond the parameters of any Pentium, and ignite rabid jealousy within every Intel beneficiary who’d witnessed their precious self-assembled synergies slide down further down 3DMark’s transient/dynamic pecking order

Any chance of reliving such cherished moments now appeared more remote than a black hole’s event horizon, yet their lingering memory induced a palpable desire to do so, regardless of the methods/means or morals.

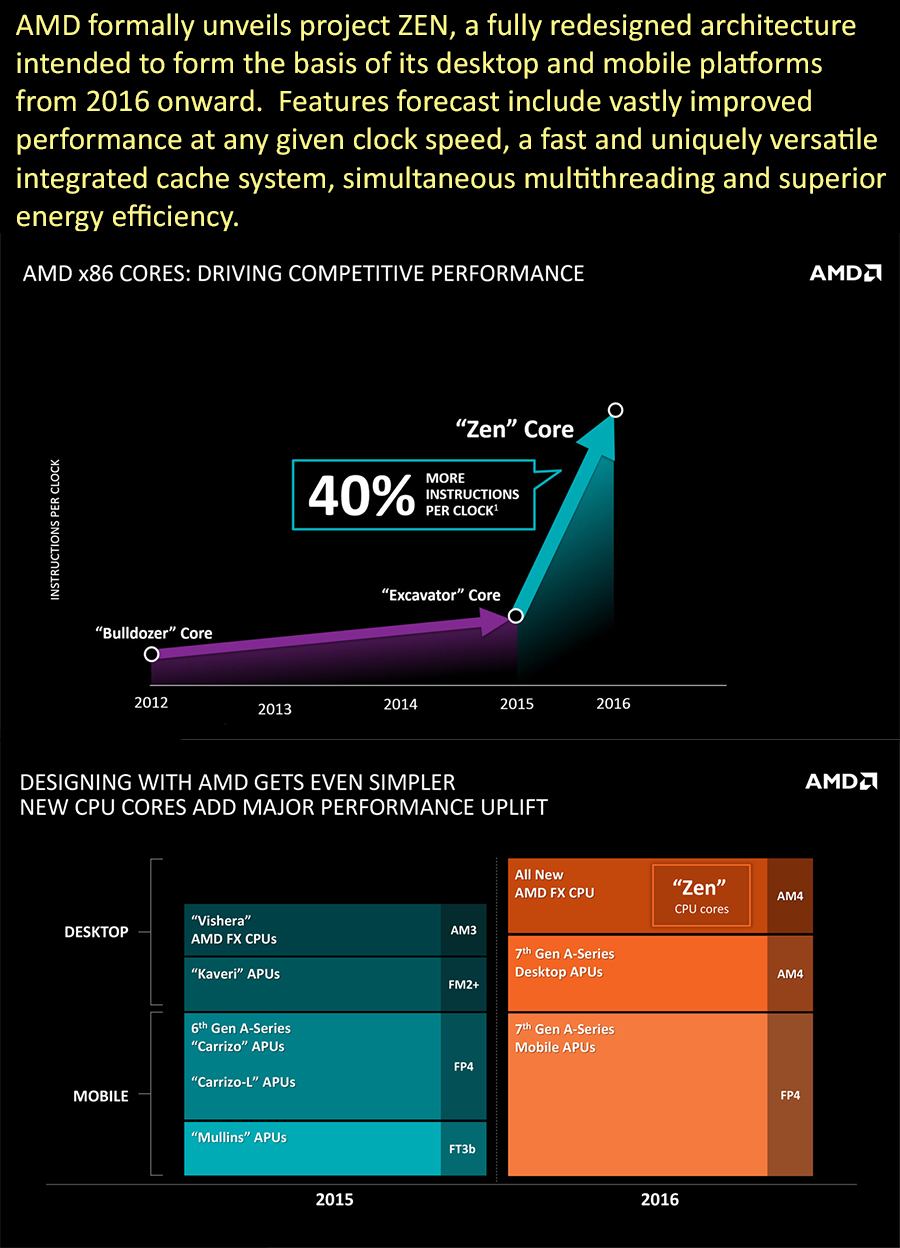

It was now August, the heady height of a sizzling Summer in 2015, the hottest on record according to NASA, throughout which our M class star energized solar panels across the Globe and seemed to be imploring a certain elemental Valley to declare carbon neutrality its unconditional reason d’etre. In a balmy Santa Clara, two fleeting months after Broadwell’s low-key emergence, the stage was set for Intel’s next genetic metamorphosis and the first of its volatile Great Lakes. In nearby Sunnyvale, as a cloudless Sky warned of their adversary’s impending attack, AMD battened down the hatches as their vexed apologists awaited news of a brisk and robust counter. Their reward was a hush so profound that it might have coaxed a frenzied zombie into a Zen like state though weeks earlier, gluttons for garish commercial proselytism who’d attended the Red team’s annual financial exposition were treated to a fanciful slideshow supposedly revealing a recipe for future brilliance. It forecast an original design, compounding raw speed with cyclical agility and incorporating a legitimate equivalent to Intel’s hyper-threading. Production details were ambiguous, though sound sources predicted that AMD’s fabricator in crime, Globalfoundries, having formed a strategic alliance with Samsung to impart 14 nanometer components, would enable their client to match Intel node for node. The project would be coordinated by one of AMDs most qualified and influential engineers, Jim Keller, lauded for masterminding the company’s K8 lineage along with several key contributions to the evolution of Apple’s mobile chips.

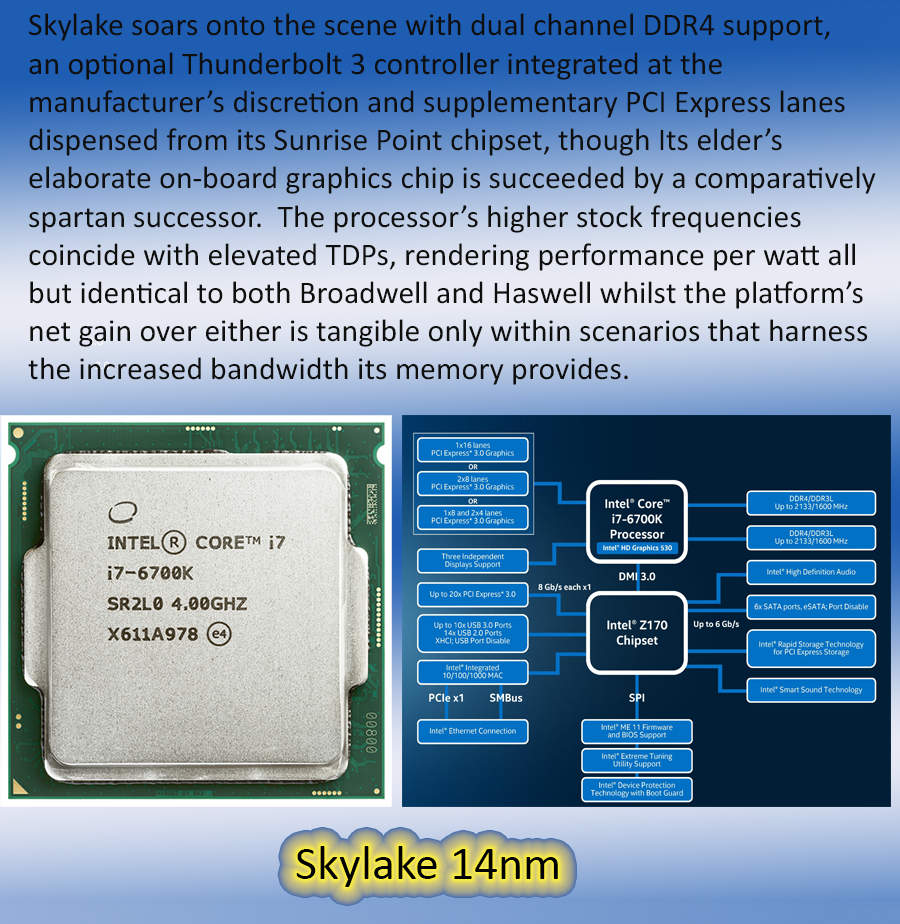

As exciting as they sounded, such ostentatious projections were far too vague and distant to win favor with itching red fingers, especially in the imminence of Skylake. All proceeded as planned for Intel’s fifth transitional “tock” since the fabled dawn of Core. Its signature chipset was ascribed the fitting alias, Sunrise Point, and gifted its adopter with a gamut of tantalising trinkets. Chief Amongst them, endemic DDR4 support with a certified entry frequency of 2133mhz, and a prolifically upgraded south bridge which substituted Lynx point’s puny allocation of eight obsolete PCI lanes with a liberal helping of twenty derived from protocol’s third generation. When combined with the processor’s innate consignment of sixteen and a direct media interface four times more capacious than before, this allowed systems to be accessorised with a synergy of USB devices, expansion cards and conventional hard drives, whilst leaving plentiful bandwidth to mobilize multiple M.2 SSDs, either separately or as bootable RAID arrays, with a lesser likelihood of bottlenecks. Once motherboard moulders had worked their interpretive miracles, contemporary embellishments such as USB 3.1 and and Thunderbolt 3 were initiated by extravagant auxiliary controllers, not least Intel’s home grown Alpine Ridge, most notably championed by Gigabyte.

Yet where novel perks thrived, there were old ones revoked. The Iris Pro graphics chip that was Broadwell’s defining asset had been abruptly discharged in favor of a rudimentary HD 530 GPU, deprived of dedicated memory and scarcely eclipsing Haswell’s house visuals. This scant substitution likely stemmed from Intel’s economic savvy yet publicly, it was attributed to the innocent and plausible assumption that purchasers would pair their acquisition with a discrete video card. Regardless, several documented tests demonstrated that even under such circumstances, as soon as labour turned to leisure, Broadwell’s Brigadier i7-5775C, with its abundant EDRAM designated as level 4 cache, consistently outpaced Skylake’s squadron commander i7-6700k. Moreover, when disregarding its chip-set’s fineries, the benefits Skylake held over its architectural predecessors boarded on the indiscernible . Its die was less than a tenth slimmer than Haswells. Its i5 and i7 embodiments housed the same quantity of cores and level 3 cache. Its higher transistor count aroused a derisory IPC bonus, and whilst its factory frequencies bested those of Broadwell, a power surcharge verging on 40 percent was required to initiate them. In fact, Skylake’s official TDP of 91 watts narrowly exceeded that of the Haswellian Devil’s Canyon and despite wearisome hours combing BIOses for every critical catalyst, even the most transcendental tweakers fell shy of justifying the chip’s gluttony. Whether in its stock state or overclocked, the collective gain provided by Intel’s present machination/formulation equated to Bob Cratchit’s Christmas bonus and only when partnered with DDR4, did a miserly minority of productivity applications exhibit tangible improvements. The prevailing consensus was that an upgrade would shortchange all but those whose towers of circuitry had survived at least one presidential term, where infallible Sandy-Bridges could be mercifully relieved of their arduous existence and escape yet further torture at the behest of owners who’d vehemently resent replacing a vacuum cleaner that was old enough to remember two divorces.

Intel’s technological drip feed was masterclass in calculated profiteering, though as before, such a scenario persisted by virtue of AMD’s apparent ineptitude. Now was the perfect opportunity to rise to the occasion and staunch their hemorrhaging user-base, to restore faith amongst floating voters with greenbacks to fritter, to intercept their foe’s relentless monopoly with a bona fide alternative to Skylake. The Yuletide season expired with no sign of stocking stuffers from Lisa Su’s band of merry elves. AMD’s upmarket renovation remained work in covert progress and in February 2016 their interem offerings were so innocuous, that many diligent chroniclers failed register their release. Steamroller had surreptitiously morphed into Excavator, a second and genetically overhauled 28mn iteration from which spawned a solitary super-budget APU entitled “Carrizo”. Designed for the Boulton chip-set’s FM2+ socket, the X4-845 retailed for what most enthusiasts would casually shell out for a swanky keyboard and moreover, less than half the bounty of Steamroller’s higher-clocked offshoots, with a negligible sacrifice in performance. If nothing else, this acute surge in efficiency was an encouraging twist of irony for Bulldozer’s fourth and final curtain call, and signified that AMD’s clandestine renaissance would ultimately guide them to rosier pastures.

As green saplings bloomed into verdant forests and ebony soil sprung rainbow foliage/golden fields, Intel’s swelling conceitedness further compounded their prohibitive pricing policy. On the cusp of Summer in 2016, Broadwell’s extremists rolled into retail and this time the traditional triplets flaunted a revised naming scheme and fourth member, though it was debatable precisely which was the introductory product, or whether the gap it was intended to fill actually existed, the reason behind its inclusion became obvious upon a cursory glance at the quartet’s kingpin. 3.2 billion transistors squeezed onto a die one third slighter than its elder, 25 megabytes of triple tier cache and the first deca-core concoction outside of Intel’s illustrious enterprise sector. For a processor of such stupendous prowess, it was perfectly reasonable to presume that addicted elitists would donate a little more generously, even if the levy alone was enough to acquire a reputable laptop, an antique writing slope and a hundred shots of death wish coffee. To temper the sting, and in contrast to Broadwell’s mainstream counterparts, Intel magnanimously offered their $1700 i7-6950x as a stress-free swap-in for existing Haswell-E adopters.

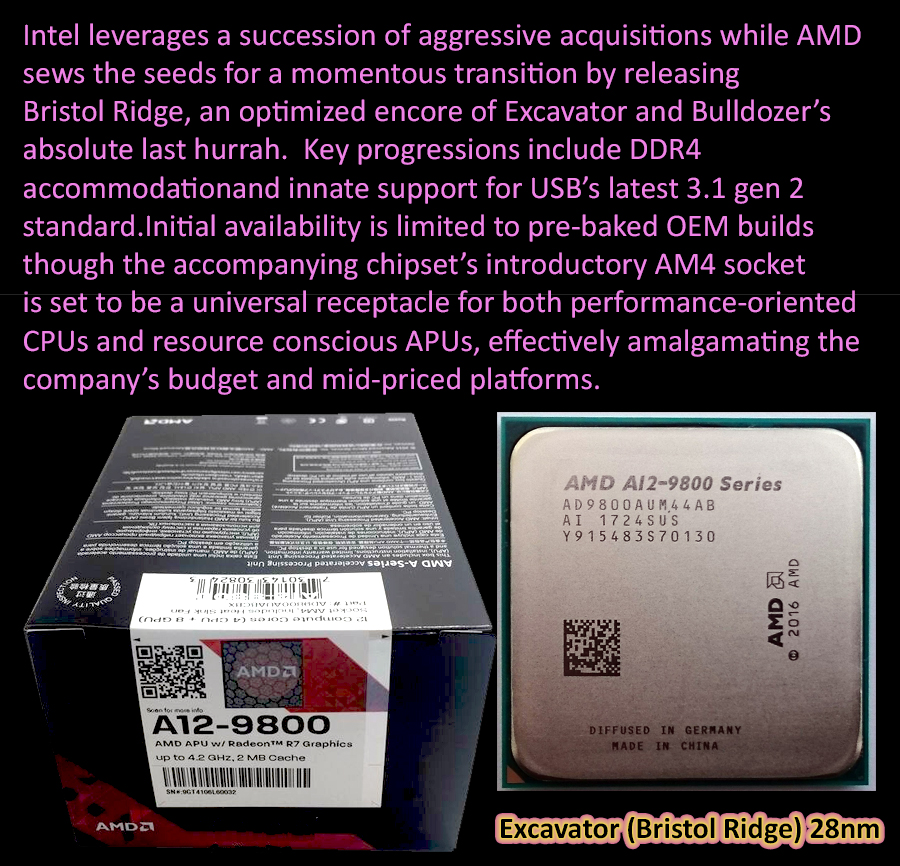

Despite a gross profit approaching forty times that of AMD, whom after income tax and operating costs were trading at a loss, Intel remained gravely dissatisfied at being placed behind Apple, Samsung and Microsoft in Forbes Magazine’s annual seeding of top tech titans, and in between the surgical dicing of semi-precious silicon, the Megladon of Megahurtz engulfed five further companies, expanding ruthlessly into the lucrative realms of 3d Video production, drone technology and machine learning. Elsewhere, the corridors of Red Central stayed inscrutably serene until at last, as sweet chestnuts revealed chocolate conkers and regal oaks shed fifty shades of golden brown, Global Foundries forces rumbled into life and rendered Excavator’s reincarnation, Bristol Ridge, a cascade of more than a dozen APUs requiring an inaugural socket and chipset to function. Motherboards based upon the nameless B350 platform were initially enigmatic and proprietary entities, present within a handful of factory integrated PCs produced by such OEMs as Hewlett Packard and available off the shelves of select hypermarkets . While neither these systems nor their constituents possessed the brunt to fulfil greater demands than those posed by the humble home office, the foundations for a promising future had taken root. The Bristol Ridge Brotherhood yielded sizable and proportionate power savings relative to Clubs Kavari and Godavari, with their ringleader, the a12-9800 and its subsequent “PRO” epitome, both managing to preserve their ancestors’ aggressive clock frequencies, with 30 watts to spare for six LED downlights. Beyond this was a polished graduation to DDR4 with officially sanctioned speeds of upto 2400mhz while the distinctly unremarkable AM4 socket, was destined to be to a vessel of legendary significance.

The remainder of the year lapsed with Intel wallowing in oceanic affluence while its fringe fraternity perceived nothing over the fence to induce their defection. Defiant disciples whose Bulldozers were now longer in the tooth than a walrus welded to woolly mammoth, were exasperated by AMD’s monotonous focus on the economy-class consumer and the sporadic stream of feeble solutions it engendered. The consensus across rumour mills that these products were stepping stones to a club-class that would be worth the agonizing wait, and probably feature paper napkins tastefully draped over head-rests, failed to alleviate their impatience. Upon learning that AMD had been re-enlisted by Sony to formulate the mechanics of their imminent Playstation 4 PRO, many accused Intel’s infernal nemesis of selling out/kowtowing to the tawdry populace, and arrogantly shunning the resourceful connoisseurs that had earned them acclaim of a more wholesome variety.

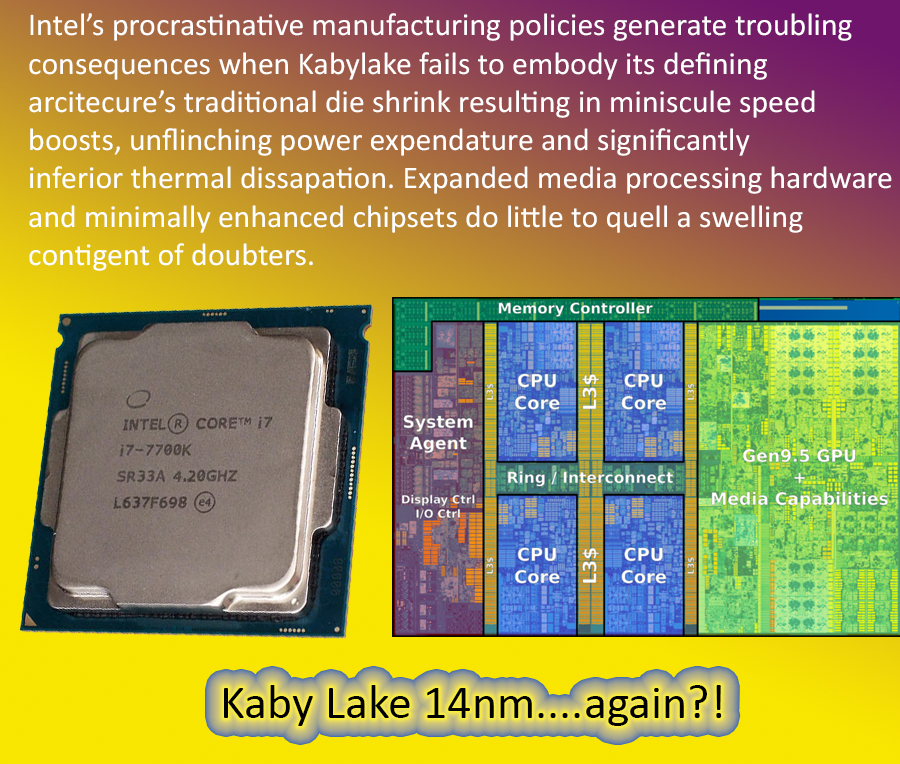

As the strains of Auld Lang Syne spiraled into a skyline peppered with fountains of iridescent pyrotechnics and thousands of pixelated influencers faced the grim prospect of feigning a further year of excitement over sticks squares and rectangles that were a bit faster and a lot pricier, Intel delivered some squares that were a bit faster for a few dollars more. Kaby Lake to Sky Lake was what Broadwell had been to Haswell and Bridge Ivy to Bridge Sand and the Westmeres to the Nehalems, and Platoon Penryn to Core, save for one cataclysmically consequential detail.

Semi Conductor companies such as Global Foundries and TSMC profit by entering into licensing agreements with contemporary enterprises like AMD, and Nvidia to manufacturer their “high level” chip designs. Beyond embodying the “high-level” templates pioneered and licensed by their clients, these fabricators are also obliged to develop their own “low-level” methodology to optimally utilize each progressive process node. This vital engineering procedure pertains to the physical characteristics of the silicon wafer and transistors used to honour their contracts and the effective mass production of each. In the event that a fabricator fails to attain acceptable yield rates or encounters insurmountable technical difficulties during development, it has been known for them to enter into subservient partnerships with rival fabricators, who grant them the rights to use their “low level” techniques to serve “high level” clients in return for collective and collaborative use of their facilities. Intel, by contrast, boasted their own fabrication plant, and assuming sole responsibility for both the conception and physical implementation of their technology was critical to the company’s success since they were never forced to rely upon a third parties to meet deadlines for high volume production, a luxury that even Apple could not savour.

What was amiss with Kaby Lake? Where was the rogue stitch in an otherwise seamless tapestry. How exactly did the fruits of Intel’s freshest fabrication differ from former “die shrinks”. The answer epitomized irony, for Skylake’s condensed successor had not shrunk a single nanometer. What had been forecast to tread the catwalk in a figure hugging size 10, emerged in a tactically tailored size 14 and the break in Intel’s refining traditions/patterns of refinement could be traced back to 2015, when the company postponed installing the apparatus necessary to realise its 10 nanometer design and subsequently announced that it would delay bulk production until the following Summer. When the story surfaced , only famished forum hawkes actively fuelling the next thousand post topic gave it a second glance, now, in the stark light of its repercussions, rumours began to permeate the tech community’s teeming masses and soon evolved into febrile speculation of a semi-conductive glass ceiling within Intel’s hitherto mercurial universe.

Curiosity was rifer than ever as to what treasures lurked at the bottom of Lake Kaby? How much extra had Intel coaxed out of a node that had seeded an unprecedented third lineage? On paper, the launch lineup appeared uncannily similar to Skylake’s. A pair of i7s, one vanilla mid-carder with a top-billed twin touting the magic K to denote its malleable multiplier, and both housing 8 megs of cache. In the middle, a scantily budgeted i5, also unlocked, but two megs less hospitable. In all three instances there were minor speed bumps but also, identical TDPs. In the optics department, Kaby’s “HD630”, was a step-up from Skylake’s native assets and featured indigenous H.265 video decoding, but for a reductionist seeking something robust enough to supplant a standalone graphics card, it remained leagues below Broadwell’s ground-breaking Iris Pro GPU, and the luxury of hybridized EDRAM now appeared terminally relegated to the company’s eco-centric mobile products.

Once the hollow hype had subsided and hundreds of test benches stood strewn with ravaged review samples, ruined pumps, ruptured radiators, empty cans of caffeinated water with a squirt of cough syrup to make it taste expensive and heaps of half-baked builds exhibiting the sort of shoddy workmanship that they‘d sneeringly shame rookies for practicing, but were now compelled to apply themselves in pursuit of a million early hits and monetary sustenance from their sponsors. Some took over 5000 words to laboriously analyse dissect product which shuffled its purchaser a paltry five percent further up the proverbial Hall of Frames but two dozen degrees closer to Dante’s inferno. Kaby Lake’s soaring temperatures were initially thought to be a symptom of the same rudimentary thermal compound that had plagued Haswell, but meticulous reviewers who considered voiding warranties their moral duty quickly attributed this anomaly to an excess of the silicone adhesive used to secure the CPU’s heat-spreader to its simmering die. It was also vividly evident that the Kaby Crew slim advantage over Skylake correlated directly and solely with their elevated frequencies, thereby confirming suspicions that Intel’s efficiency curve had plateaued and cycles of instructions, were spinning on the spot.

Throughout the history of competitive sports, there have been athletes who shone on their day and others who shone through the darkest clouds/nights, and true greatness is rarely accomplished without instinctive resilience. When challenged over an episode of game changing fortuity good fortune, many consummate exponents at the peak of their profession will respond with the skeptical mantra, “You make your own luck”. The expression harbours of variety of contextual definitions, but if an honoured world champion were forced to expound they might well assert, “To make your own luck is to be there whenever your opponents luck runs out.” With Intel’s luck at its lowest ebb and its processors resembling cautious quarterbacks attempting run out the clock, the opportunity to equalize with a last minute touchdown could not have been more inviting.

Two months later, as March’s wild gales whaled in frenzied harmony with hoards of hungry Red revolutionists, AMD’s arduous pilgrimage through the corporate wilderness looked poised to yield redemption. Having braved a crippling five year conflict to ignite the souls of their master’s benefactors, could six fleets of battle-scarred Bulldozers finally relinquish their duty with dignity? Would their salvation be a blissful retirement inside the retro-builds of fanatical collectors, who would preserve their honour with heartfelt retrospectives, proving that in the face of such savage opposition, their campaign was far worthier than many critics had conveyed? And from a mound of smouldering embers, would a flock of phoenixes rise to form the ZENith of Intel’s worst nightmares?

A preview of AMD’s rejuvenated regal heritage had taken place the prior Summer at the prestigious Electronic Entertainment Expo and its architectural descriptor “Zen” dated back to 2015.

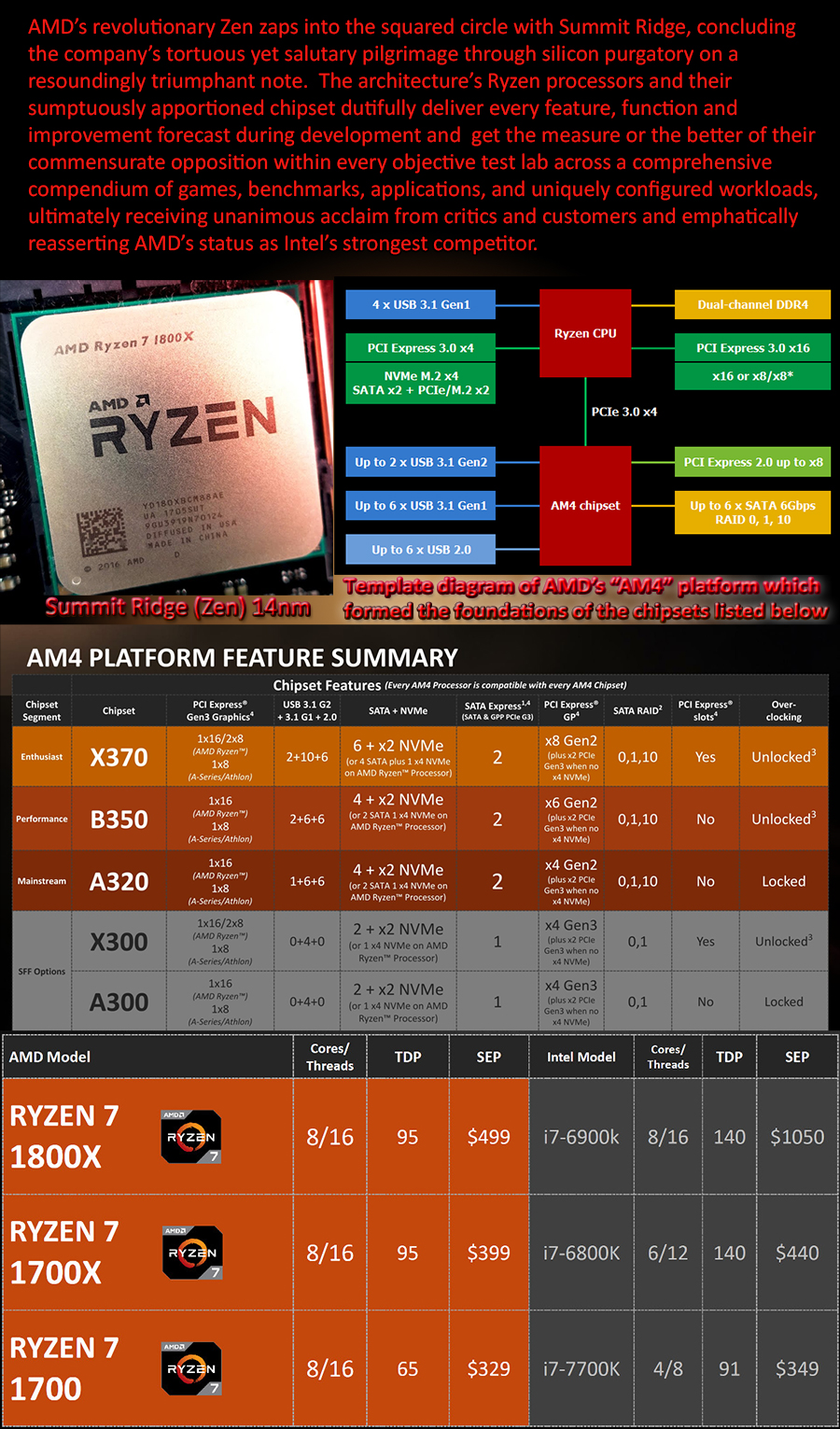

Now, the resultant litter of “Ryzen” branded CPUs, devised by AMD, manufactured by their dependable spin-off, Global Founderies and moulded from Samsung’s super-efficient 14 nanometer finfet design, unanimously bore the moniker, “Summit Ridge”. As promised, Zen’s primary manifestation had germinated from virgin roots and throughout its extensive period of development, AMD substantially detailed a bevy of inaugural features, mostly inherited from Bristol Ridge but implemented on a far grander scale. The platform’s premier chipset was, like its welterweight forerunner, bereft of a fashionable pseudonym, but the x370 needed nothing other than its arresting specifications to spark a flurry of intense publicity. There were supplementary USB ports, expanded storage connectivity and accommodation for multiple graphics cards. But Zen’s defining feng shui resided under the heat-spreaders of clan Summit Ridge and exposed the silent inroads AMD had etched into royal blue territory during Intel’s unparalleled spree of success.

By a telling coincidence, Zen’s fervently hyped arrival welcomed a trio of processors and true to their word, AMD had supplanted Bull-Dozer’s legally disputed integer cluster complex, with eight fully independent cores endowed with dedicated floating point units and in so doing, had also doubled the payload of Kaby Lake’s headliner. Summet Ridge’s maiden triforce also marked the genesis of Symmetric Multi Threading, AMD’s long-awaited interpretation of Intel’s Hyper-threading. However, the most ingenious element within AMD’s radical revival was woven into Ryzen’s Infinity Fabric.

Organically functional, like a honeycomb and finer than golden gauze spun by Rumpelstiltskin, this omni-directional data interconnect intuitively facilitated communication between the CPU’s multiple dies, its integral memory, USB and Sata and controllers, the chipset exchange and PCI-subsystem, the latter to which was served a tantalizing 24 lanes of third generation bandwidth. Since Zen’s inception, AMD had bullishly targeted an IPC increase of forty percent over the abdicating “Excavator” and at the stroke of midnight on St’ David’s Day when embargoes dissolved into digital purgatory and a swarm of tech touters published reviews they had concocted two weeks/336 hours earlier, it became evident that what doubters had dismissed as reckless optimism was, if anything, tactical prudence. When pitted against the Kaby Lakers, Summit Ridge’s three pronged skirmish proved remarkably effective. The last heavyweight desktop clash between Intel and AMD had taken place almost three years earlier, when the Haswell’s hellacious Devil’s Canyon had locked cores with Piledriver’s volcanic Vishera in what resulted in a landslide points victory for the Intel reared chip. The i7-4970k had streaked into leads exceeding 50 percent for games and lightly-threaded applications and was only pegged back by the FX-9590 once workloads pushed both processors to their productive extremes.

In what was the effective rematch, Summit Ridge’s venomous Ryzen 1800X went die to die with Kaby’s Lake’s menacing hereditary champion, the I7-7700k. The pair tipped the scales at equal price tags, with the Ryzen shedding a concessionary fifty dollars one week before the weigh-in. Their TDPs were within watts of each other but The Ryzen provided larger portions of cache, with the initial two levels being divided into dedicated segments for each core and the third, a liberal 16 megabyte insurance buffer, communally allocated to two quad core clusters, officially designated “core complexes”. Kaby’s Lake’s cache resources were roughly half as spacious, though its tertiary tier of 8 megabytes was apportioned equally and exclusively to individual cores, affording Intel’s chip a lower latency than its rival’s in cases where the latter’s reserve was more than one quarter occupied. The terms had been finalized, the contracts were signed and a showdown eras the in the making was poised to send shockwaves throughout its parent industry and captivate the collective conscience of a bloodthirsty crowd. Had the event been a pay per view promotion, subscribers would have been charged the purchase price of both processors just to observe their ring entrances. As a feverish silence enveloped over the binary bell tolled and fifteen furious rounds of rendering , stress tests, and time-demos began. Following a flurry of savage opening exchanges, it was apparent that AMD had obliterated Chipzilla’s seismic advantage. In the gaming stakes, some scorecards declared that Prince Kaby had clung on to its master’s crown whilst others ruled the contest a technical draw on account of the Ryzen’s smoother frame rates, specifically in titles that were demanding enough to approach the parameters of Intel’s chip.

The mere fact that Kaby-Lake’s four hyper-threaded cores was scarcely sufficient to expunge micro-stutter was alarming, though few could have estimated the devastating impact that Summit Ridge’s weightier physique would have during the contests’s losing stages once play ceased and productivity commenced. AMD’s revitalised savior landed a barrage of withering blows across a plethora of popular applications. Progress bars accelerated as export times tumbled and, in spite of faster frequencies and higher over-clocks, Kaby Lake’s ring-leader was bullied backwards onto the ropes, bewildered by the attack and powerless to counter until workloads relented to single cores. Ryzen’s ace captain rocketed up every roll of honour, leapfrogging three lineages of Intel’s finest pedigrees, scything through Cinebench mosaics, sweeping aside Crona’s intricate luminaries, eviscerating V-ray ‘specular assault courses and dispatching detailed Blender imagery like a blowtorch through butter. Its breath snatching scores doubled those of the lumbering Bulldozer, and propelled the Scarlet Avenger 50 percent clear of a choking Kaby Lake. As the closing minutes ticked away and both combatants cranked-up their voltages, raised their ratios and boosted their buses in endeavours to scrape crucial frames and shave critical seconds, it was the peerless vigour of Summit Ridge’s relentless eight punch onslaughts that proved decisive in the eyes of the judicious public.

The resurrection had succeeded, the comeback was complete and a deluge crimson confetti descended upon an audience of delighted and deflated technocrats. For AMD, patience and perseverance had paid priceless dividends, and operation Ryzen had catapulted The Ruby Rebels back into contention for computer hardware’s most coveted crown. Intel’s historic streak was broken, though their Empire remained all pervasive, enveloping vast swathes of digital real-estate and casting a towering shadow over their enemy’s insurgence. Affluent enthusiasts whose livelihoods depended on deadlines, despised progress bars more than bankruptcy, or who would die if they slipped onto page two of Geekbench’s order of merit, were still bound to Blue extremes bearing extortionate bounties, and the server sector remained an impregnable Intel stronghold.

Having levelled one battlefield, could AMD now transform the momentum they had mustered into a triumphant revolt against their tyrannical oppressor? Would they at last bring broad and lasting liberty back to a monopolized market and serve customers in every niche with alternatives that would compute cycle for cycle, watt for watt and pound for pound? Could Intel finally crack the code to the next elusive node, and ensure that AMD’s resurgence was as short-lived as a scam artist’s morals? Would hindsight ultimately condemn Ryzen as nothing more than a fleeting flash of electrons extinguished by sands of time? Answers to such prophetic questions were certain to tie up the loose threads of a long and epic saga.